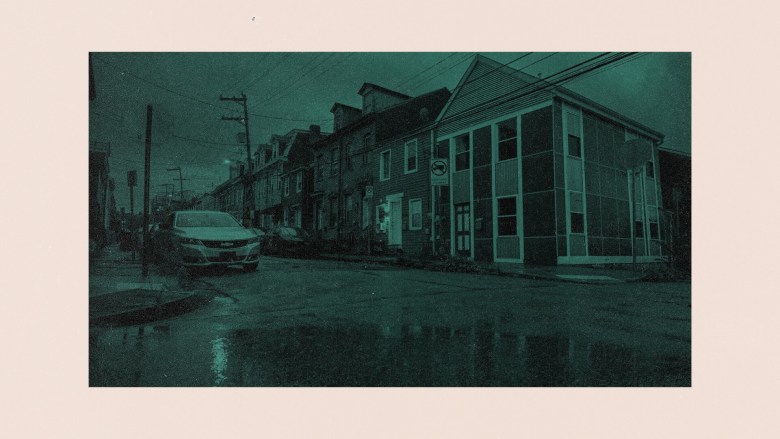

When Zakary Littlefield bought a home on a small dead-end street overlooking Pittsburgh’s South Side, he didn’t suspect that he’d be forced to sell it just three and a half years later.

He noticed the cracked pavement when he purchased the property. The road had cratered and the asphalt was, inch-by-inch, crumbling down the hillside.

Unable to navigate the shrinking, craggy edge, standard city garbage trucks soon stopped picking up his trash, later replaced by smaller refuse vehicles. Drivers no longer delivered to his doorstep. In the back of his mind a thought persisted: “My road may be gone tomorrow.”

Littlefield’s home, recently renovated and nestled along Newton Street in the South Side Slopes, is one of 11 properties on that street that the City of Pittsburgh intends to buy and then retire in an effort to mitigate the risk of landslides.

In Pittsburgh and throughout northern Appalachia, the combination of a soft, clay-laden geology and a precarious, tilted topography raise the likelihood of landslides. With more frequent and intense rainfall expected in a warming world, the probability of damage to property and people is likewise expected to swell.

The home buyouts, funded with $1.2 million from the Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA], are one way that local governments can counter potential catastrophes. In other parts of South Pittsburgh, nearly $10 million in additional FEMA funds, plus millions more from the city, will be spent this winter to reinforce slopes deemed worth saving.

Maintaining Mount Washington

The slopes of Mount Washington have for years attracted concern from city officials.

In February of 2018, setting off what would become one of the wettest years in recent record, a landslide destroyed a home on Greenleaf Street in Duquesne Heights, spilling debris onto Route 51 and closing the thoroughfare. To the east, Mount Washington’s William Street has been closed and crumbling since 2018 and now resembles a narrow walking trail rather than the two-lane roadway it once was. At the bottom of Reese Street, the hillside is slowly sliding down a steep incline above a walking trail in Emerald View Park and Norfolk Southern’s railroad tracks.

“There’s a lot of transportation infrastructure that has been impacted or could potentially be impacted by some of these landslides,” said Eric Setzler, the chief engineer at Pittsburgh’s Department of Mobility and Infrastructure.

Slippy slopes: Pittsburgh, built on slide-prone riverbanks, could face a deluge of impacts from climate change

Some of the existing landslides on Greenleaf, William and Reese streets have been temporarily stabilized and the supports have been holding, Setzler said. But by the end of the spring, these three failing slopes will be permanently buttressed by the FEMA investment.

The point of the stabilization projects, Setzler said, is to secure the hillside to protect residents, their homes and transportation infrastructure that could be damaged should a catastrophic event occur, ideally, “ensuring stability for decades to come.”

The city, which is contributing $3 million to the $13 million total project cost, anticipates work will begin this winter after the construction contracts are settled. The work is expected to finish by April 2025, and Setzler said the most noticeable disruption will be the closure of Greenleaf Street for much of the duration.

More rain, more slides, more costs

“Ten years ago, this wasn’t really even an issue that was on the city’s radar,” said Jake Pawlak, deputy mayor of Pittsburgh. That’s not because city administrators weren’t attentive, he said, but “because we weren’t having nearly so many landslides, which have really emerged as a major infrastructure challenge and safety challenge in the past decade.”

Now the number of potentially unstable slopes far outweighs the city’s capacity to fix them.

“It’s a real challenge,” Pawlak said. “It’s a risk to people. It’s a risk to our economy. It’s a risk for infrastructure.”

In 2018, when historic rains drenched Southwestern Pennsylvania, the city spent more than $12 million on cleanup from landslides. “We want to be more proactive,” said Setzler.

He’s targeting imminent or ongoing slides in Elliott, Riverview Park, Morningside, Perry North and South and the Hill District. If heavy rains persist, more could follow.

The city has begun to allocate more money to fixing and preventing landslides. The 2024 budget calls for $4.6 million for slope failure remediation and $8 million next year. After that, the budgeted numbers taper to $2.3 million and $2.5 million and $2.7 million from 2026 and 2028. The decrease in 2026 does not represent a de-emphasis on landslides, but rather a normal ebb and flow of project funding cycles, Pawlak said. He expects more funding to be allocated to the budget in the years to come.

Even as more money flows to landslide prevention, the investments that these projects require, Pawlak said, could not be met without state and federal partnerships.

The Mount Washington-area projects and partnership with FEMA, which pays 75% of the bill, he said, is a “great first step in what we hope to be an ongoing relationship in addressing these issues.”

Building buyout

When Littlefield met with city officials about his home on Newton Street, they told him the risk was higher than they’d like for people to be living there, and the cost of repair too high to justify.

“The outcome of that meeting was effectively that it would be cheaper to buy the houses there from residents that were on the road than to fix the road,” he said.

The city offered fair value, Littlefield said, about the same amount that he paid for it, and he took the offer. “It would be impossible for me to sell the house to anyone else, so I kind of felt like it was the only reasonable option,” he explained.

The city applied for another grant from FEMA to acquire the houses, through a program designed to eliminate high-risk properties, but the agency hasn’t yet confirmed the funds. With options limited for protecting private property, the buyouts allow city government to mitigate private risk through acquisitions and demolitions.

“It’s an opportunity for people whose homes are at risk or severely damaged to start fresh and also for the government to reduce the risk by eliminating that property,” said MaryAnn Tierney, the regional administrator for FEMA.

When the federal funding was announced in December, Tierney toured the city’s at-risk hillsides.

“As we think about climate change and we think about areas that are at risk for climate change, it’s not just coastal communities,” Tierney said. “It is communities like Pittsburgh, where you see the effects of concentrated rain on these very significant and steep slopes.”

She applauded Pittsburgh for its efforts, but recognized the remaining challenges.

“The city is doing all of the right things,” Tierney said. “They’ve prioritized this. They’re seeking grant dollars. They’re putting their own money behind it. They’ve had a massive engineering effort to think about this. … They should be commended for recognizing and trying to take proactive steps to address it.”

Photographs by Quinn Glabicki.

Quinn Glabicki is the environment and climate reporter at PublicSource and a Report for America corps member. He can be reached at quinn@publicsource.org and on Instagram and X @quinnglabicki.

This story was fact-checked by Sarah Liez.