Student enrollment in Pittsburgh Public Schools [PPS] dipped by 270 during 2023 – a slower rate than previous years. And some schools clocked unexpected growth.

Despite this year’s slower decline, though, the district of 18,380 is projected to lose an additional 5,000 students by 2031.

Resources are split unevenly in the district, leading to some schools with higher concentrations of economically disadvantaged students receiving less money per pupil, disparate student outcomes, uneven academic offerings in high schools, a lack of experienced staff in schools with a majority of Black and low-income students – and magnet schools that may accelerate some of those inequities.

The latest data suggest, though, that some struggling schools are making progress that’s attracting new students. Of the district’s 54 schools, 18 saw increased student enrollment last year.

Among those are Perry High and Milliones 6-12, known as UPrep — two schools characterized as under-resourced.

Ted Dwyer, district chief of data, research, evaluation and assessments, said this is the first time since 2013 that PPS has seen any enrollment increases in K-5 schools.

James Fogarty, executive director of advocacy group A+ Schools, attributed the individual upticks – and the slower overall rate of decline – to expanded programming, community partnerships and building leadership.

“We're seeing where schools are being responsive to community desires and needs where we're increasing opportunities and access to resources,” Fogarty said.

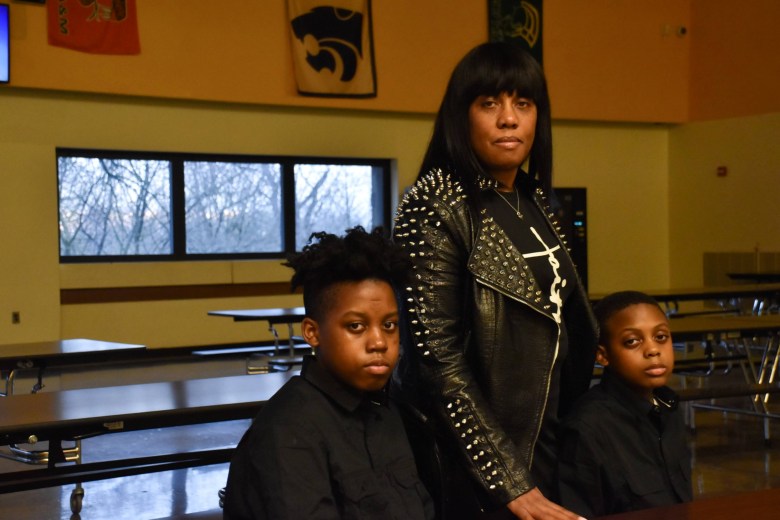

Jayla Manison’s daughter, a senior, has been at UPrep since sixth grade. Manison opted to continue her daughter’s high school education at UPrep because of its diverse program offerings, resources and opportunities. Her daughter is now the class president, has completed enriching internships and has a college offer.

How magnet schools attract some, repel others, and contribute to Pittsburgh’s polarized education system

“I would have never been able to find those connections had I not kept [my daughter] at Prep,” Manison said. “And I have friends with children in different schools at PPS and to me, I feel like it's the best as far as opportunities goes because they have so many programs.”

Fogarty said schools like Perry and UPrep are slowly changing their perceptions as under-resourced schools because teachers and staff are present in the community and not just talking about programs, but delivering.

Changing the narrative in two under-resourced schools

Perry and UPrep offer the fewest AP courses in the district. Perry enrolls 428 students, with 88% economically disadvantaged. UPrep is the smallest high school in the district, enrolling 315 students, with 87% economically disadvantaged.

So why are they growing?

At Perry, Forgarty said, partnerships like the University of Pittsburgh’s Justice Scholars Institute [JSI] have attracted families and students to enroll. Through JSI, students can enroll in seven college and university-level preparatory courses in high school aimed at enhancing college readiness and graduation rates.

Perry, which added about 75 students this year, also has a strong and stable staff that is engaged with the community, he added.

Molly O’Malley-Argueta, principal at Perry, said the school has focused on creating positive experiences in the classrooms through community partners like the Children’s Museum of Pittsburgh and the Carnegie Science Center.

The school has also changed its approach toward parent engagement by holding in-person back-to-school and curriculum nights where parents informally meet staff members. The staff does separate outreach for ninth graders by going door-to-door and delivering school supplies.

Student enrollment at UPrep increased by about 25 students this year. Fogarty said The Pittsburgh Promise coaches are heavily invested in offering academic support at UPrep. The school also has invested in counseling staff to support student academic advancement.

Eric Graf, principal at UPrep, believes his four-year tenure at the helm has helped him develop strong ties to the community. In the coming years, Graf wants to continue investing in the school’s magnet programs, bring in more STEM and arts programming and set higher academic expectations for students in hopes of further increasing enrollment.

Inequities between schools might be contributing to enrollment dip

Jimena Salas had two children in PPS Montessori K-5. This year, as her daughter, Ada, started sixth grade, she decided to enroll her at the Environmental Charter School [ECS] instead of returning to the district.

School locations, demographics and resources tip the scales on academic outcomes in PPS

However, ECS was not their first choice. Salas wanted Ada to enroll at PPS arts magnet CAPA, which requires an audition, or STEM magnet Sci-Tech, which involves a lottery. Ada couldn’t get in. Their remaining options were PPS Obama (another magnet), Arsenal 6-8 (their neighborhood school), or ECS. Of the three, Salas believed ECS was a better fit for Ada as she transitioned into middle school.

CAPA’s and Sci-Tech’s high test scores made Salas want to enroll her daughter in those schools. She said if Obama or Arsenal offered the type of programming and had high student achievement, she would have considered staying in the district.

Obama and Arsenal were termed low-achieving schools in 2023 by the state Department of Education and did not meet its standards for proficiency levels in standardized tests. CAPA and Sci-Tech, on the other hand, had some of the highest proficiency rates in math, English and science.

Magnet school enrollment has remained steady over the last five years but the proportion of white students admitted has increased.

In the last two years, Salas said, she knew at least 15 students who moved out of Montessori to go to private schools or ECS. Charter school enrollment has increased by 24% in the last five years.

“It seems like the students that have the best grades, they all go to a certain school and then the other schools are kind of left at a lower level,” said Jimena.

Housing and resource gaps are contributing factors

At other high schools, enrollment has dipped despite them offering more programming and community involvement. Westinghouse, Allderdice and Brashear saw enrollment dips of around 70 students this year.

Westinghouse, one of three schools participating in the JSI program, has seen a high turnover in leadership, with four principals leaving in the last five years, including one at the beginning of this school year.

Dwyer said the number of students in kindergarten and first grade has increased after the dip during COVID-19. Around half of children born in the city end up starting kindergarten in the district.

“We are a microcosm of what's going on in the city and what's going on in the county. So we're very concerned about it,” Dwyer said.

Fogarty said housing affordability is another major factor that pushes families out of the district.

“We're not building a lot of new family housing,” he said. “It's just not happening at the pace where a family is looking at, ‘Do I stay here or do I move into Wilkinsburg where there's bigger housing for less money that I can rent or Penn Hills?’”

Dwyer agreed, saying housing is an issue because PPS serves a largely low-income population.

Allderdice and Westinghouse, 3 miles away, are worlds apart in AP classes, teacher experience, student disadvantage

“If a family doesn't have a stable income, or if someone who's renting a house increases the rent by some astronomical amount, families aren't gonna be able to afford that,” he said.

For families like Salas’, that choose to move out of the district during the transitioning years of sixth or ninth grades, the district needs to change the perception around schools and engage them to retain those students, Fogarty said.

Fogarty said outside of districtwide marketing and communications, PPS should focus on community presence and experiences within the schools.

District spokesperson Ebony Pugh said PPS is working to change the negative narratives around certain schools by investing in marketing and telling positive stories. The district has hired a new director charged, in part, with “narrative transformation,” and is working on empowering schools to tell their stories and share strategies for increasing enrollment.

A need for socioeconomic integration

The district is developing a strategic plan to address inequities in different schools and may consider school closures to improve student outcomes and reduce costs.

PPS is operating at 54% of its building capacity and has an excess of 17,000 classroom seats. Only two schools in PPS, Colfax and Allderdice, are entirely full. Dwyer said this has led to some extremely small schools with less flexibility and higher costs.

“We're going to have to have a conversation about what exactly it is that we need, what the design principles are and design the district around that, based on community input and the board,” he said.

Fogarty said PPS needs to have bigger and socioeconomically integrated schools instead of smaller, neighborhood schools with high concentrations of Black and economically disadvantaged students and students with disabilities. He added PPS should consider creating schools that, like magnets, can attract families across neighborhood lines.

“If we keep the current footprint and current funding structure of the system, we know that this system is fundamentally racist at its core,” said Fogarty. “We know that the system is fundamentally broken and the status quo creates disparate outcomes for kids, predominantly based on their socioeconomic status but also based on race.”

Lajja Mistry is the K-12 education reporter at PublicSource. She can be reached at lajja@publicsource.org.

This story was fact-checked by Elizabeth Szeto.

The Fund for Investigative Journalism helped to fund this project.