When a victim of gun violence is brought to UPMC Presbyterian in Oakland, a nurse in the trauma center might rush to their station and pick up a business card from Richard Garland.

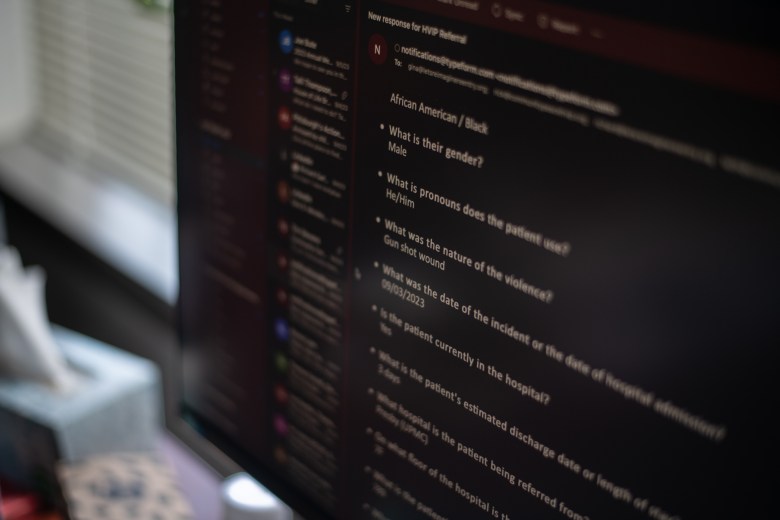

They might use a smartphone to scan the QR code on the card, which pulls up a form they can fill out and send to Garland’s team at Reimagine Reentry, where he serves as executive director. The form provides crucial information about the victim, including their name, age, where they were shot and whether they’ve consented to receiving services from the nonprofit, which is based in the Hill District.

Within 24 hours, a violence prevention coach from Reimagine will visit their bedside and offer services such as therapy, job training and housing assistance. The goal, said Garland, is to intercept victims before they retaliate — a practice that could result in fewer gun-related homicides and help stop the cycle of violence in Allegheny County communities.

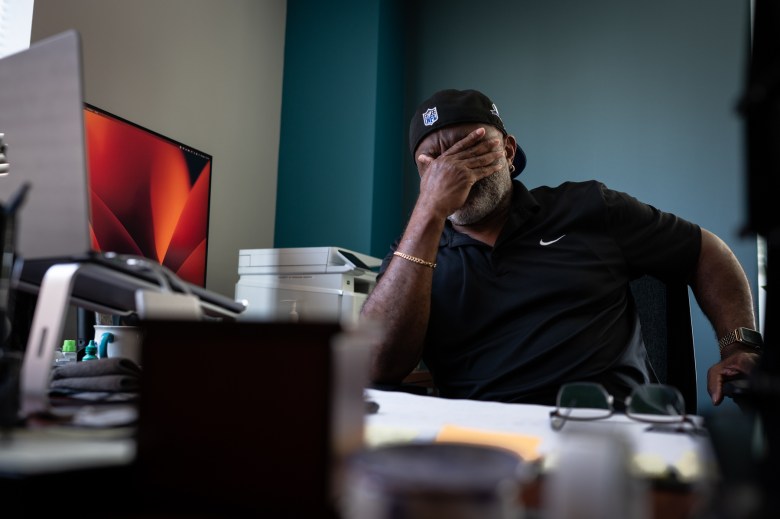

Garland and just one other person on his team, Gina Brooks, did this work on their own for years. It would take them up to three days to reach a victim’s bedside, which meant fewer opportunities to help before they were discharged. But an infusion of cash from the county — more than $370,000 over the last year — has changed that. Garland was able to pay for the QR code system and hire three staffers for Reimagine’s hospital-based violence intervention program. Now his team is able to reach victims across four hospitals in less than a day.

“Being able to go to these hospitals at the drop of a hat has changed things significantly,” Garland said.

“Just us being able to have this funding has enabled me to take things to another level.”

A QR code for Reimagine Reentry’s CommUnity Peace hospital-based violence intervention program, on Thursday, Sept. 7, 2023, in Gina Brooks’ Reimagine Reentry Hill District office. The cards are attached to nursing stations in the city’s trauma wards, and a simple scan starts Reimagine’s violence prevention efforts. (Photos by Stephanie Strasburg/PublicSource)

It’s been six months since the county announced it would commit $50 million over five years to reduce community violence, which happens between unrelated people outside their homes and disproportionately affects youth in communities of color. The Allegheny County Department of Human Services [ACDHS] selected 13 local organizations through two requests for proposals to carry out its plan: to treat violence like an infectious disease. The effort adapts programs that have proven to be successful in other cities — including three from Chicago — to “high-priority areas” in the county.

Read more: FLIR camera in hand, watchdog traverses Washington County, revealing invisible emissions

An act of violence is rarely limited to one neighborhood, said Rev. Paul Abernathy. “If we don’t have a coordinated effort across community lines, it will be difficult to address the violence in our region.”

Abernathy is CEO of the Neighborhood Resilience Project based in the Hill District. The county appointed the organization to be a “countywide convener” and awarded it more than $177,000 over the last year to bring all stakeholders together to collaborate and share resources.

Leaders at some of the involved anti-violence organizations told PublicSource they’re hiring staff and building out programs. Some said the funding is a good start, but isn’t enough to address the root causes of violence such as poverty and structural racism. Others aren’t counting on the funding to continue beyond the county’s five-year commitment.

Read more: Vote delayed on proposed Allegheny County housing health code changes

‘This is the most we’ve ever gotten, but it still isn’t enough’

Lee Davis stood on Margaretta Street in Braddock on a sunny afternoon in late August. Behind him was a memorial at the edge of a grassy patch called New Hope Green Space, which belongs to the local Baptist church.

On the night of Aug. 27, two teens were shot and killed on the spot, which was now adorned with candles, stuffed animals and pinwheels that spun in the wind. Nazir Parker and Rimel Williamson were both 17-year-old seniors at Woodland Hills High School. A third teen was found shot in a nearby home and was taken to a hospital. Davis said he was in stable condition.

Read more: Study on health benefits of Neville Island coke plant closure raises questions about Clairton

Davis is the director of violence prevention for Greater Valley Community Services [GVCS]. The organization will receive more than $1.3 million from the county over the next year to adapt two models to the Mon Valley: Cure Violence, which trains trusted community figures to work with at-risk youth, and the Rapid Employment and Development Initiative [READI], a transitional jobs program for at-risk men.

Davis and about 30 members of the Greater Valley Coalition Against Violence gathered at the site of last month’s shooting to peacefully object to what happened. The practice is recommended by Cure Violence, which calls for violence prevention workers to “change norms” by visibly responding to every shooting in their coverage area.

“People just drive by and beep and see that you’re out here,” he said, waving at a school bus as it drove past. “It lets them know that you care.”

During an interview that took place before the shooting, Davis said the county’s funding will help GVCS “enormously” as it continues the violence prevention work that he said is helping to reduce gun-related homicides in the area. There were 7 homicides in the Mon Valley in 2020 — the lowest number since 2007, according to the county Office of the Medical Examiner. But homicide numbers have climbed since then: There were 11 reported homicides in the area this year through July, according to the county’s homicide dashboard. The number of countywide homicides — most of which are gun-related — jumped from 93 in 2019 to 128 in 2022. The victims are mostly Black men and boys.

Davis said GVCS has hired 10 people for its Cure Violence program — called CURE V.I.B.E. — and plans to hire eight people for its READI program, called Achieving Change Through Transitional Employment Services [ACTES]. Both programs will be staffed by site supervisors, program managers, therapists and outreach workers.

But “I see a disaster” if the county doesn’t continue the funding beyond five years, he said, predicting that community violence will increase if funding for violence prevention dries up. “We probably need 10 or 15 [years] because we all know this stuff didn’t happen overnight. This is the most we’ve ever gotten, but it still isn’t enough.”

From top left: Lee Davis leads a meeting of the Greater Valley Coalition Against Violence in Braddock on Aug. 29; Davis stands outside the building after the meeting; community members created a memorial on the spot where two teens were killed in Braddock on Aug. 27; Davis waves at a school bus during a Cure Violence response to the shooting on Aug. 31. (Photos by Stephanie Strasburg/PublicSource)

Rashad Byrdsong, who mentored Davis in the 1990s, agrees that the funding doesn’t go far enough. Byrdsong is the founder and CEO of Community Empowerment Association in Homewood. The organization received more than $131,000 from the county over the last year to provide gun violence victims with therapy and other supportive services.

“Even though $50 million was appreciated, you’re going to need much, much more to address this plague mainly in the Black community here in Pittsburgh,” he said, adding that the funding won’t erase “years of social neglect” and the structural racism that “incubates violent behavior” by keeping Black and Brown people from “having the same rights and access as everyone else.”

Read more: Daycares in the Pittsburgh area sound the alarm as insurance companies pull coverage

‘We don’t have unending resources’

Erin Dalton, the director of ACDHS, doesn’t dispute concerns about the limits of the effort.

“We don’t have unending resources, but we make a lot of those investments and care deeply about making sure people have their basic needs met,” she said during a late August interview. She added that the kind of funding and policy changes that address the root causes of community violence should happen at the federal level.

Abernathy said the programs the county selected aren’t meant to address the root causes of community violence. “It’s really focused on disrupting the violence in real time,” he said, adding that the county’s commitment is “an opportunity to leverage additional investment” to transform formerly redlined communities that have experienced “trauma over multiple generations.”

“I don’t care about all this funding if we’re not actually preventing violence.”

Dalton said the county’s decisions to renew funding over the five-year period are contingent on each awardee’s performance. That includes their ability to get violence prevention programs up and running and to keep risky situations — such as fights in schools — from escalating into something worse.

“I don’t care about all this funding if we’re not actually preventing violence,” she said.

It’s hard to measure the outcomes of violence prevention programs, said Steven Albert, a professor of behavioral and community health sciences at the University of Pittsburgh. Gun violence is relatively rare, so a cluster of violent acts around one event — such as a party — can ruin the data.

The main drivers of community violence are poverty, the availability of guns and “an underground economy that enforces using violence,” said Albert, who co-leads with Garland the Violence Prevention Initiative at Pitt’s Center for Health Equity. It’s why he believes strong gun-control measures would have the biggest impact in communities affected by violence.

“But I think these violence interrupters are critical,” Albert said. “They don’t get the pay or recognition they deserve. And the funding for them is a good idea.”

Dalton said $50 million is the largest amount of money the county has invested in violence reduction, which has typically been funded by private foundations in the past. She said she'd hope to see “all violence ... eliminated,” adding, “That hasn’t happened yet. But I do expect that if these programs are working well and reducing violence in these communities, then we may be able to move on to a lower-level effort.”

The county’s plan was structured in a way to encourage coordination, not competition, among the organizations that were awarded contracts, said Jessica Ruffin, deputy director for ACDHS’s Office of Equity and Engagement.

‘Money is always the issue. Hopefully it doesn’t run out.’

An Lewis speaks to Garland from Reimagine almost every day.

Lewis is the executive director of Steel Rivers Council of Governments, which received more than $900,000 from the county over the last year. A portion of that funding will be used to implement a Cure Violence program called Cure Mon Valley in Homestead, Duquesne, McKeesport and Clairton. She said her organization used the funding to hire 17 new staffers to “intervene before shootings and killings occur” across those four communities.

While the council of governments has worked to change the Mon Valley through infrastructure improvements, it’s never run a violence prevention program. That’s where Lewis’ regular conversations with Garland come in.

“We really are curating these programs together,” she said, referring to Cure Mon Valley and Garland’s hospital-based work. “We have to coordinate because the people Richard’s team are responding to are coming from our communities,” she added.

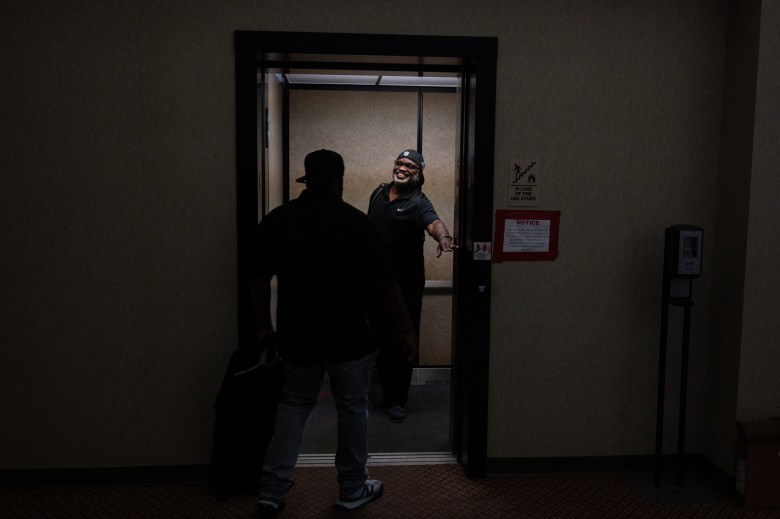

From left, Richard Garland’s email shows one of the gun violence patient information forms he receives through his organization’s hospital-based violence prevention initiative. “Everybody’s coming together as an Allegheny County unit, all the different organizations,” said Gina Brooks, director of violence prevention for Reimagine Reentry. Garland holds the elevator for one of his fellow violence prevention team members as they leave for a meeting. (Photos by Stephanie Strasburg/PublicSource)

“[Reimagine’s] QR code was brilliant,” Lewis said, adding that Cure Mon Valley is considering deploying its own QR codes in the communities it serves. Since the Cure Violence model aims to detect and interrupt conflicts, the codes would allow community members to quickly send the team information about people who need help.

In Stowe-Rox, Cynthia Haines and her team at Focus on Renewal are building an ACTES program that places participants in jobs at local businesses.

“So people are opening up their arms, their hearts, and more than that, their place of business for these men.”

Employers weren’t always so eager to hire Focus on Renewal’s clients, said Haines, who is the executive director of the McKees Rocks-based organization. But funding from the county — about $1.3 million over the last year — allowed her to hire a job coach and supervisor to help participants succeed in their new roles. Their schedule includes four-hour workdays, cognitive behavioral therapy and guest speaker sessions to “open their minds up” to different career possibilities. At least 20 local businesses have committed to hiring them, she said.

“So people are opening up their arms, their hearts, and more than that, their place of business for these men,” she added.

Mike Skirpan and his team at Community Forge in Wilkinsburg joined the effort when ACDHS officials told them they were having trouble finding a provider to launch a Cure Violence program in the eastern part of the county. Skirpan hired 16 people, including a program manager and two site supervisors who manage violence interrupters throughout the area. The team will peacefully resolve conflicts and connect families and individuals to services such as therapy, SNAP benefits and workforce development programs.

“I am very hopeful that continued investment in these communities happens after five years,” said Skirpan, Community Forge’s co-founder and executive director.

Back in the Hill District, Garland’s team is working to keep nurses and social workers informed about what’s happening on the streets. They give presentations to hospital staff throughout the county every six months, he said.

“But money is always the issue,” he said. “Hopefully it doesn’t run out.”

Venuri Siriwardane is PublicSource’s health and mental health reporter. She can be reached at venuri@publicsource.org.

Stephanie Strasburg contributed reporting to this story.

This story was fact-checked by Tanya Babbar.

This reporting has been made possible through the Staunton Farm Mental Health Reporting Fellowship and the Jewish Healthcare Foundation.