In the early hours of Sept. 2, 2005, my family’s sense of normalcy was interrupted by an aggressive banging on the door. I stood at the top of the stairs as my brother answered only to be pushed aside by four police officers. They pointed at me, stating I was under arrest.

My brother demanded to see a warrant, which they eventually presented after threatening to arrest him for obstruction of justice. I was allowed to put on shoes before being handcuffed, along with my nephew, and escorted into the back of a police cruiser.

It was the start of my long and challenging journey through the criminal justice system. I was just 16, wrongly accused and horribly unprepared.

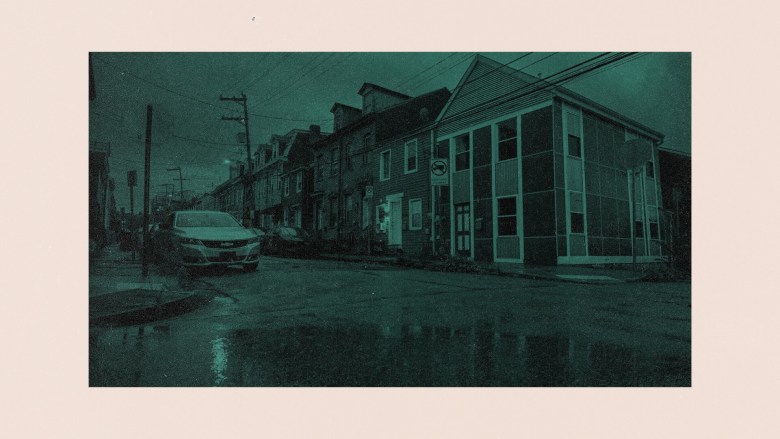

Even as the county moves to reopen the Shuman Juvenile Detention Center – ostensibly to get kids out of the Allegheny County Jail – my own experience with incarceration shows that the entire approach to law enforcement of youth needs to be reexamined beyond the location of their detention.

Naive beliefs, feelings of insignificance

Two weeks after my arrest, following my release on a $3,000 cash bail, I stood in front of Pittsburgh City Council, speaking about my experience in the Allegheny County Jail.

This was solely at the urging of my mother, who had been deeply affected by my arrest and incarceration. Her anger was visible, and she made it known to everyone who would listen, from the Carnegie Police Department to the corrections officers at the jail and my public defender. She believed my story needed to be heard and that I was the best person to tell it.

As I spoke before Council, I remember feeling a mix of nervousness and encouragement bolstered by the presence of my mother and aunt. However, the response was disheartening as only one council member seemed to listen attentively, while the rest and the audience ignored me completely. I felt that my experience was common enough to be insignificant in the grand scheme of things.

It wasn’t until 2019, when I joined the Bukit Bail Fund, that I began to see value in what I had been through, and to understand the context.

In November of 1995, the Pennsylvania Judicial Code was amended under Act 33, allowing minors accused of certain crimes, such as armed robbery, to be charged and tried as adults. This legal backdrop meant that instead of being taken to a juvenile detention center, which I had anticipated, I found myself treated as an adult instead of the child I was.

Reflecting now, I see parallels between my story and those of many young people I’ve supported over the years who have been similarly charged as adults and placed in jail. The closure of Shuman and the subsequent doubling of the juvenile population in ACJ underscore the urgency and importance of my work in advocating for these young individuals and their families.

My firsthand experience with the criminal legal system at such a young age was a rude awakening. Before that, I had held a naive belief in the fairness and justness of the law – that police required substantial evidence to charge someone, that judges were impartial, and that, according to the U.S. Constitution, one was innocent until proven guilty. However, my arrest, based solely on an accuser’s word against mine; my original bail of $25,000, which was arbitrarily set significantly higher than that of my co-defendant; and my subsequent treatment in the Allegheny County Jail quickly dispelled these beliefs.

‘Is that it?’

From the moment I arrived in the jail, I felt the climate of negativity and the undertone of violence. I didn’t receive an iota of respect from the jail staff as I was ordered from one single cell to another. I waited hours at a time between the logistical procedures of the intake process. I remember dozing off and being awakened by the kick of a corrections officer before he ordered me to the next station.

Over the next several days, I was searched, arraigned, photographed, questioned and strip-searched before being forced into the red uniform that marked me as an inmate and taken upstairs to the housing units. When I think of the time I spent in the ACJ, I recall the deplorable conditions that make it among the deadliest jails in the country.

For almost a week, I was kept in isolation, locked in a cell for 23 hours a day without explanation. My pod was not exclusive to minors, leading to me eventually mixing with the adult majority. I lost weight because the jail refused to accommodate my vegetarian diet, leaving me malnourished and vulnerable.

I witnessed rampant bullying and abuse by both the jail staff and the residents that underscored the culture of the jail itself. I watched a man get beaten unconscious and lose control of his bladder while others looked on in amusement. As he was taken away on a stretcher, my name was called for my first visit. It was my mother, who was unable to conceal the pain caused by seeing her youngest son enduring conditions she hoped I would never have to.

After my preliminary hearing, my bail was reduced from $25,000 to $3,000, and my family was able to pay a percentage to a bail bondsman to facilitate my release. Over the next few months, I fought my case in criminal court until my attorney filed a petition for decertification, which allowed my case to instead be tried in Juvenile Court.

After I was decertified, I started the legal process again, but this time as a juvenile. I was arraigned in a courtroom at Shuman, placed on home detention for the duration of the case and assigned a new attorney who I didn’t meet until the day of my trial.

I remember being shocked by the differences between juvenile and criminal court. If found guilty in criminal court, I could’ve been sentenced to 5 to 10 years in a state correctional institution. In juvenile court, I would’ve been placed in the Community Intensive Supervision Project.

Even after the massive reduction in potential sentencing, I still refused to accept a plea bargain and admit guilt for a crime of which I was innocent. When the judge dismissed the case, I remember everyone casually gathering their belongings and exiting the courtroom. I looked at my lawyer and asked, “Is that it?”

It was.

There was no apology from the court for what my family and I had endured for over a year. There was no accountability for the person who falsely accused me, or the officers who failed to conduct a thorough investigation. There was no recompense for the time and money spent to prove my innocence. There was nothing.

What if the money went to engagement?

Time can never be reversed, and trauma can never be undone. My family and I didn’t skip around our experiences; we had no choice but to persevere through them.

Even 18 years later, a forceful knock on my mother’s door triggers back spasms so severe she’s left lying on the floor.

I was forced to live with the stigma of being labeled a criminal, enduring constant surveillance, harassment by police, illegal searches and several unjust arrests. The problems didn’t stop when my charges were dropped. Most recently, in May 2020, I was violently arrested along with 45 others during a protest in Pittsburgh of George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police.

None of these experiences, however, impacted me as much as my initial arrest, which thrust me into adulthood. For a Black person in America, adulthood means coming to terms with being perceived as part of an inferior social class, undeserving of fair and equal treatment under the law. I once accepted this as the norm, but I now recognize it as unacceptable.

Today, my work with organizations like 1Hood and Community Care & Resistance In Pittsburgh [CCRIP] is driven by my experiences and those of my community. We aim to create a network of care and support, advocating for those entangled in the criminal legal system, and challenging its punitive nature. We support individuals and families in several ways, from bailing people out of jail to providing direct aid upon their release. Our weekly presence outside the ACJ, offering cash, food, clothes, and most importantly a sense of humanity, is a small but significant step toward change.

My story, while personal, is not unique. It reflects the broader narrative of mass incarceration and systemic racial and social oppression in the United States. The disproportionate representation of poor and Black people in prisons and jails is a testament. In Allegheny County, while Black people make up 13% of the population, we’re consistently populating two-thirds of the jail. The prevalence of plea bargains, often accepted regardless of guilt, highlights the systemic flaws and the punitive nature of our criminal legal system. My co-defendant, of whose innocence I am convinced, pleaded guilty and was sentenced to three to six years in prison, the first of numerous jail and prison terms he’s served.

The potential reopening of Shuman,with Adelphoi chosen as the private operator, raises significant concerns, given the lawsuits against them and the lack of transparency and public input in the county executive’s decision-making process.

Organizations like 1Hood Media, CCRIP, the Abolitionist Law Center, Community Forge, the Bukit Bail Fund, the Thomas Merton Center and Food Not Bombs Pittsburgh exemplify the kind of community support and engagement that genuinely make a difference, and could do even more if they had a fraction of the funding spent on incarceration.

In sharing my story, I hope to shed light on the realities of the criminal legal system and the urgent need for a system based on restoration, transformation and care. I hope to inspire others to work toward a justice system that is truly just and equitable for all.

Muhammad Ali Nasir, who goes by his emcee name, MAN-E, is the advocacy, policy and civic engagement coordinator at 1Hood Media and founder of Community Care and Resistance In Pittsburgh. He can be reached at muhammad@1hood.org.