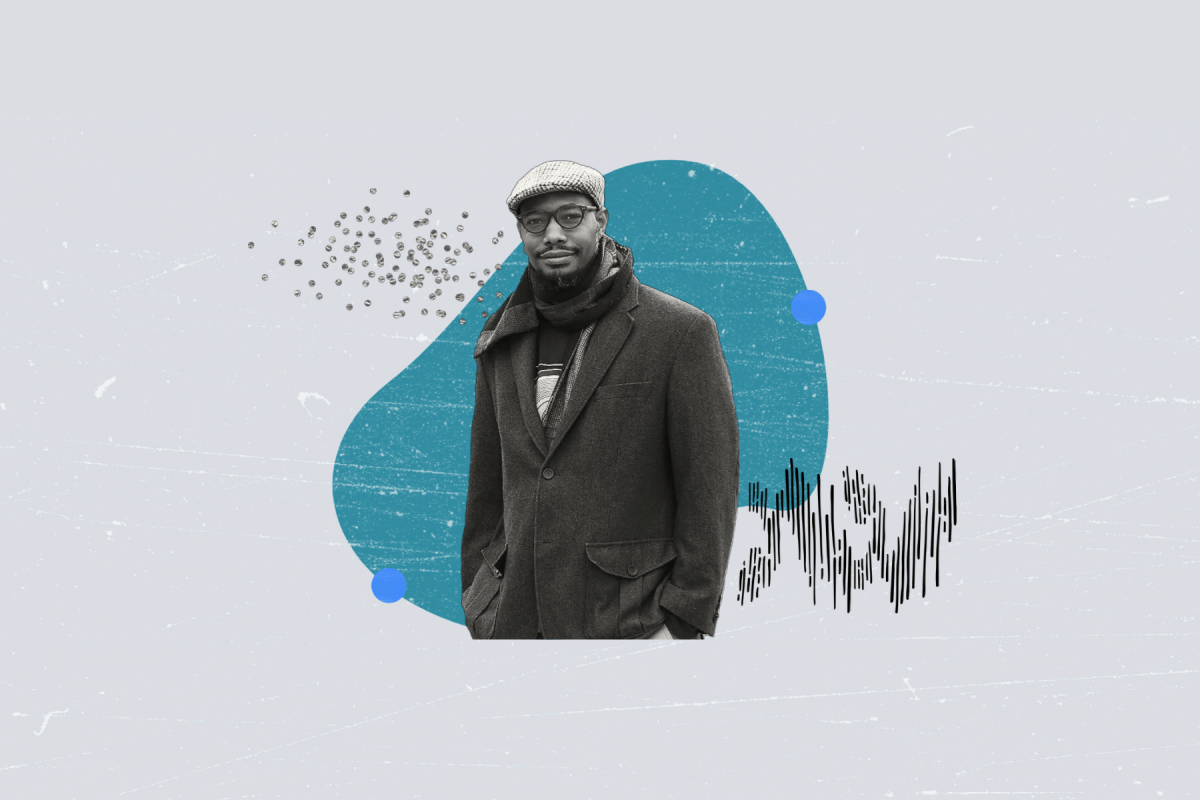

Meet Ali R. Abdullah as he explains the significance of being an African-American Muslim in the Pittsburgh region and what you should know about Pittsburgh’s role in Islamic history in the United States.

For a deeper look into what Ali uncovered about his own family’s connection to religious history in the area, check out the story by PublicSource faith and religion reporter Chris Hedlin: “Pittsburgh was once a Black Muslim refuge.”

TRANSCRIPT

Jourdan: Hello, everyone, welcome back. It’s me, your host, Jourdan Hicks, community correspondent for PublicSource. Welcome back to another episode of From the Source. Now, this week, we have yet another interesting Pittsburgher who you should meet and someone who you could learn a little something from to expand your worldview of our area and the people who bring our region to life. Unlike previous episodes of From The Source, this episode is not a standalone piece. “Pittsburgh, A Black Muslim refuge,” written by our religion reporter Chris Hedlin, focuses on the Abdullah family of Braddock and their family’s deep connection to the spread and practice of Islam by Black Americans in our area. On the audio side, you’ll meet Ali R. Abdullah, the source for Chris’ story and a proud father, girl dad, Muslim, African-American man who wants to challenge the monolithic representation of Black and Islamic-practicing people in our area and how they’re depicted and why it was important for him to learn and teach and record his own family’s history.

Ali: Unfortunately, as a people, we really don’t connect to that like in a tangible way. Some of us do, don’t get me wrong. Some of us do. Some people go back to the point of no return. People do DNA tests. Some people do all kinds of different things now, but in large part, it’s not something that we sought out and not only is it not something that we sought out, I think it’s something actually a lot of us have run away from. You know what I mean? You know, because of the psychological brainwashing that’s been done to us, you know, to tell us, you know, certain things are bad and, you know, just the whole mindset that.

Jourdan: It’s almost like you have to go through this confrontation and unlearning period to really understand the deep interruption that racism and oppression has had on a lot of our family lineages, family lines, family histories, our culture, the way we relate to each other, how we move around the country, around the world. And it takes a lot of fortitude, commitment and bravery, really, for someone to want to do a deep dive into history and to see on paper if they can find it, the lives that their family members led in spite of the circumstances that they were placed in.

Jourdan: Unfortunately for Black Americans and many Black people around the world, it’s not as simple as opening up the family tree and connecting the branches and going backwards line by line, and then at the same time living in an era where there are probably more positive affirmations about Black life and Black families in the media, but also at the same time, there’s a social justice movement calling to the value of Black lives, so it’s like these dueling dispositions. Just like what the world is telling you and who you believe you are, while you’re trying to find the truth about your family.

Ali: So the double whammy, you know, they have I mean, from, you know, all the standpoints you could fathom basically denigrating us by propping themselves up at the same time. Right? So that’s like a double whammy psychologically. Everything associated with you is bad and everything associated with us is good, and this country is the best. No other civilization has ever existed that’s ever been better than here. Like that’s basically what was put out. Right? And so and a lot of people like, you know, I think I mentioned to Chris, unconscious infiltration. You just eat up what is being projected to you, right? You’re just like, OK, yeah, I make sense. I’m you know, I roll with that. And so especially if you have nothing to compare it to.

Jourdan: Right. Right. What is it to you about your family history, legacy, that makes it important, valuable, worth sharing outside of the fact that it’s yours?

Ali: I mean, it is a totally separate thing from myself. I mean, it is obviously because I’m connected to it, but, you know, if I stepped away from it, it is something that, you know, I think is I guess the sole reason is it’s very unique. The whole population in the United States when we talk about history, I think is it’s a key piece of history that’s left out like Islam in general within the context of American society. Just as one basic example is that Morocco was the first country to recognize the United States’ independence. So that was like, you know, a Muslim country was the first country to recognize America’s independence. If we take just from a historical perspective, just looking at Islam and then, I think getting into some of the things we were just talking about with African Americans in our history and people trying to trace their lineage back or trying to understand who they are fundamentally in all these aspects of their culture — religion, social status, types of jobs, they had types of education. I think this is all connected to that. I describe myself in a lot of ways as being the typical African-American guy. But then this situation in so many ways is atypical, right, for an African-American family is that, you know, Islam is something that they chose over with the mainstream religion was at the time and then continue with that within the last several years. Me and some of my friends had discussed this. And it’s like this is like going on. So our generations of Islam, even here in Pittsburgh, from my research, I will say, is probably over 100 years just here because we’re among African Americans. So that’s something that no, you know, many people don’t know or are totally oblivious to.

Jourdan: And if you could briefly kind of give me a feel for like, what is the history of Black Islamic people, Muslims in Pittsburgh?

Ali: It really started with Indians from India who were here and they basically proselytize the Ahmadiyya faith. For many African Americans, that was one of your first inclinations of Islam. And they became Ahmadiyya Muslims, and then when they found out about Sunni Islam, then basically they became Sunni Muslim. But also that you have the Nation of Islam. Right. Which is not, it’s basically a pseudo-Islamic movement which was created here in the United States. Right. So, you know, that wouldn’t be considered Orthodox Islam, but it took one name and maybe certain basic attributes. And there’s a lot of lines that run through these different movements I’m talking about right now. Marcus Garvey’s UNIA Movement, Universal Negro Improvement Association. So my grandfather, he was actually a member at one time. So if you study, it was more of a Black nationalist movement. Most of the people who were Sunni and Ahmadiyya just by default were African American because for a time, you know, just like we kind of talked about some other things, like the immigration was like restricted to certain groups and then it was open to other groups. So the majority of immigrants in the early parts of the century were very wide open to Europeans. Right? Whereas other groups, it was checks and balances. So you might have some of those groups come, but you may not have had, you know, influxes or ships of Indians coming or ships of Arabs coming or ships of Africans come in, with the exception of the transatlantic slave movement, of course.

Jourdan: So how does this inform your history today? Everything that you know, the process of realization that you went through from birth to now going from I just have an Arabic name, ‘I know we don’t eat pork’to really embracing your family’s history and legacy and stamp in our area when it comes to being prominent and proud Black Muslim people.

Ali: I think it informs who I am, and it inspires, definitely made me all through my childhood, all the way up until the time I was 25. It was like a progression. Right. But it was more about self-discovery. So it was more about trying to understand and discover who I was, a person who really didn’t grow up in Orthodox Islamic household praying five times a day or want to, you know, weekly service or celebrating different Islamic holidays like that really didn’t happen. So, you know, I had an Arabic name, you know, Islamic name, and I knew how to be poor. But that was obviously an extremely small fraction of, you know, like the lifestyle and the faith and all of that stuff. I mean, it informed me in so many different ways, like one, you know, it gave me purpose as a human being. And, you know, it put me in connection with my humanity. It gave, it gave me purpose. They gave my humanity purpose from a cultural standpoint, you know, much of what my grandparents on both sides got was probably in, which is nothing wrong with that. But it was nothing like coming from your own perspective. Same thing with our schools when kids or not only being taught by people who look like them and loved them, but also the information is coming from. Your own perspectives, right then that bolsters your education. So they they basically were getting their Islam, you know, from an Indian perspective or Pakistani perspective many times, which is fine. But it didn’t put you in contact or connect it to Africa. And so as an African-American man, when I was growing up, you know, it was one of our go-tos or a staple in my life was, and probably for a lot of Black people across the years, is Black music in general and me specifically hip-hop. And so you got that message threaded through that you got that message about being Black.

Jourdan: To learn more about Ali Abdullah’s story. Please, please, please, please, please read Chris Hedlin’s new piece, “Pittsburgh was once a Black Muslim refuge. Here’s one family’s story.” So easy read and you find out more information about the rich, deep, dynamic, diverse and inclusive version of the role that religion, people, place and movement plays in the Pittsburgh region’s history. Thank you. Stay safe. Be well y’all. Until next time. bye.

Jourdan: This podcast was produced by Jourdan Hicks and Andy Kubis and edited by Halle Stockton. If you have a story you’d like to share, please get in touch with me. You can send me an email at J-O-U-R-D-A-N at publicsource dot org. PublicSource is an independent nonprofit newsroom in Pittsburgh. You can find all of our reporting and storytelling at PublicSource.org.