Update (11/13/23): Allegheny County Executive-elect Sara Innamorato today called news of lawsuits against Adelphoi — the private, nonprofit contractor hired to run the Shuman Juvenile Detention Center — “deeply concerning,” calling transparency in youth detention “a main priority for our administration.”

“This sets off alarm bells,” Innamorato said when asked about PublicSource’s reporting on Adelphoi and the recent complaints filed against it in federal courts.

“I want to understand more of what’s going on and what we’re looking at,” Innamorato said, “and ultimately that’s why above all else, as we open up a detention facility, we have to make sure that there is public oversight like the Jail Oversight Board, that there’s community voice there, that we are investing in a way as a county so there is enough capacity there for highly trained staff, that there’s resource providers that have access — there’s just a lot of sunshine on that facility.”

Prior to Shuman’s 2021 closure, the county operated a Juvenile Detention Board of Advisors.

“The unfortunate reality is our history of administering Shuman isn’t a great record either,” Innamorato noted.

She stopped short of suggesting a reversal of the county’s contract with Adelphoi.

“We are going to look at the terms and see what we are bound to and what best serves the needs of the young people who are caught up in this system at the moment,” she said, adding that there are now “kids in the county jail and we want to make sure that we can get those kids out of that facility and into one that is specialized and geared toward the young people who are there.”

Allegheny County’s pick to run Shuman hit with negligence lawsuits

Reported 11/9/23: When Allegheny County announced in September that it would reopen its youth detention center, it praised the private contractor hired to operate it.

“Adelphoi has a proven track record as a leading and highly respected agency” in caring for “delinquent and dependent children,” said President Judge Kim Berkeley Clark, of the Court of Common Pleas, in a press release. “This is a crucial step toward creating a safer and more supportive environment for juveniles in the county.”

That record includes accusations of failing to protect children from abuse, according to two civil lawsuits filed just days after Adelphoi Western Region signed a $73 million contract to hold arrested youth at the Shuman Juvenile Detention Center.

One is a class-action complaint filed in federal court in Philadelphia, accusing Adelphoi USA — one of seven affiliated nonprofits based in Latrobe — of a broad pattern of “negligent staffing” and failing “to enact safety measures and other policies to protect the children.” As a result, according to the complaint, “vulnerable youth … were exposed to predators and abusers.”

The other complaint, filed in federal court in Harrisburg, seeks civil damages for the survivor of former Adelphoi Services employee Tabitha Dunn, who pleaded guilty to corruption of minors and endangering the welfare of children in relation to her work with a minor to whom she was assigned as an in-home worker.

The attorneys who filed the suits told PublicSource their clients experienced severe trauma while in Adelphoi’s care and allege that some of the entities are responsible for failing to protect them from harm.

It’s important that “the institutions harboring these abusers” are held accountable, said Renee Franchi, an attorney representing the young male in the case against Adelphoi Services.

David Wesley Cornish, a Philadelphia attorney, filed the class-action suit on behalf of eight plaintiffs who allege they were abused by staff at Adelphoi facilities throughout the state.

“It’s not just one or two people … that are saying this,” said Cornish. He said his clients “had never met each other,” but made similar accusations of mistreatment by Adelphoi staffers.

The lawsuits — and another filed last year against Adelphoi Village in Westmoreland County court — raise questions about the plan for Shuman and speak to broader concerns about youth incarceration, which some advocates say exposes children to physical and mental harm and the risk of abuse.

Adelphoi said it can’t comment on pending civil complaints, but takes “extensive steps” to protect the children in its care, including training and supervising its staff and reporting incidents to Pennsylvania State Police and ChildLine, the state’s call center for reporting child abuse.

“We remain committed to providing a safe and nurturing environment for every child under our care,” said Karyn Pratt, Adelphoi’s vice president of marketing and strategy development, in an email.

Clark announced in September that Shuman — which closed in 2021 after the state revoked its license — will reopen under Adelphoi management. County and court officials signed a contract with Adelphoi that month. The center could begin holding youth again as soon as this winter if renovations to the facility are completed on schedule.

Amie Downs, a spokesperson for the county, referred all questions about Adelphoi to the county’s court system. Joseph Asturi, a spokesperson for the county’s Court of Common Pleas, declined to answer questions, including how civil complaints might inform the court’s monitoring of Adelphoi’s work.

How Adelphoi landed a $73 million contract to operate Shuman

Shuman first opened in 1974 in a brick building near the Allegheny riverfront in Lincoln-Lemington-Belmar. The county managed it for decades until the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services revoked its license for multiple violations.

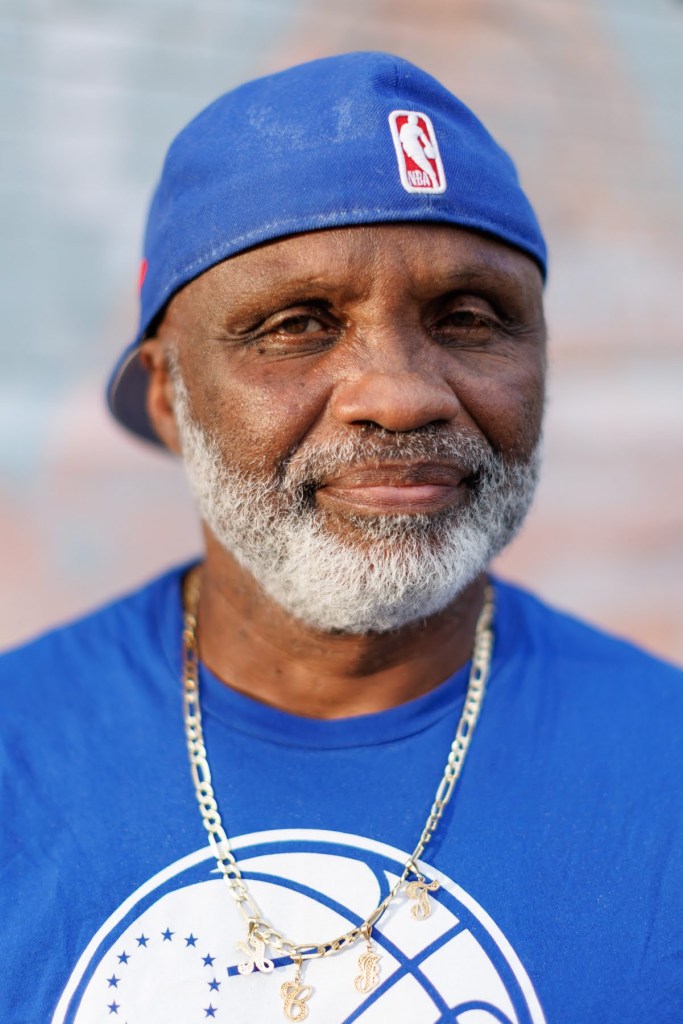

Walter Harris was 14 years old when he was first held there in the mid-1980s. He was growing up in Section 8 housing in the Hill District, and stole clothes and nice things he couldn’t afford. He was caught in a Sears store after closing time and charged with theft and trespassing.

The idea of being locked up scared him, but he calmed down after arriving at Shuman and bonding with other kids. He was sent there about a dozen more times until he turned 18 in 1988. “After that, you’re prepared,” he said, describing youth detention as an onramp to his time in state and federal prisons as an adult.

Harris’s experience gets to the core of a debate about how to help youth who’ve been arrested — and whether detention is the right approach.

After Shuman closed, law enforcement leaders complained they had no place to put youth they deemed too dangerous to be released. Pittsburgh Mayor Ed Gainey even partly blamed spikes in gun violence — without citing evidence — on Shuman’s closure. “We should have never closed Shuman without a plan,” he told reporters after a triple homicide on the North Side.

Advocates, on the other hand, pushed for approaches outside the carceral system, which disproportionately locks up Black people.

“I don’t think there is any benefit or value in incarcerating children,” said Muhammad Ali Nasir, who goes by his emcee name, MAN-E, and is the advocacy, policy and civic engagement coordinator at 1Hood Media. The county should invest in non-carceral approaches, such as working to end poverty and investing in schools instead of reopening Shuman, he said.

Under pressure from judges, law enforcement and other public officials, the county searched for a private operator to take over the site. It had “a strong preference” for one that would run a youth detention center, according to a request for proposals released last year.

Enter Adelphoi, one of the largest youth service providers in the Pittsburgh region. It submitted a proposal to reopen and provide detention services at Shuman. The county accepted the bid and drew up a contract to pay Adelphoi $73 million over five years — an annual cost that’s 40% higher than what it paid to run the facility itself.

“I don’t think there is any benefit or value in incarcerating children.”MAN-e, 1HOOD MEDIA

Under the contract, Shuman will hold youth aged 10 to 20 who are from or found in the county. They may have been charged with serious offenses, deemed aggressive or at risk of leaving an unsecured facility, adjudicated delinquent or some combination of those.

Read more about Adelphoi’s pledges to Allegheny County

County Council sued to block the plan, asserting its authority to approve or deny the use of county property. And advocates criticized the high price tag — which they said could instead go toward non-carceral programs — and lack of public oversight over the decision to reopen Shuman.

“I don’t think that taxpayers have had enough input [and] I don’t think the kids who have gone through the juvenile legal system have had any input,” said Tanisha Long, Allegheny County community organizer for the Abolitionist Law Center. “This decision was made in the dark by the courts and [County Executive] Rich Fitzgerald.”

The county’s announcement stirred “mixed emotions” in Harris, now 52 and a member of the Elsinore Bennu Think Tank for Restorative Justice. He tries to help the youth of today by volunteering for ALC Court Watch, a team that observes court proceedings, including decertification hearings. And he’ll soon launch the Pittsburgh location of Fathers on the Move, a mentorship program for youth involved in the criminal justice system.

“My mission is to make youth incarceration so rare that I have to find a new career,” he said.

Though he believes Shuman should be reopened, he can’t be sure a private contractor who’s “out to make money” shares his mission.

“Who are they?” he asked about Adelphoi. “And what is their track record?”

Who is Adelphoi and what is its track record?

The Adelphoi nonprofits operate in Pennsylvania, Ohio, New York and Delaware. They’ve served youth in the Pittsburgh region for more than 50 years.

Based in Latrobe, Adelphoi provides foster care, education, in-home services and youth detention to nearly all counties in the state. Across its seven entities, Adelphoi made over $68 million in total revenue in fiscal 2022, with its largest arm, Adelphoi Village, a group home business, pulling in about $44 million. Combined, the Adelphoi entities employ around 600, according to Pratt. More than 1,000 youth receive its services every day.

Adelphoi declined a PublicSource request to tour one of its detention centers and did not make an executive available for an interview. Pratt, the group’s marketing executive, answered detailed questions via email.

She said Adelphoi isn’t new to the county. It serves about 60 youth per year here, including those who need shelter or are in the foster care system. After Shuman closed, the county placed youth it wanted to detain in Adelphoi facilities in nearby counties, including group homes in Westmoreland County, she added.

Pratt called the lack of available beds a “detention crisis” in the region. She drew a straight line between the closure of Shuman and an uptick in youth fleeing Adelphoi’s group homes. She said non-secure group homes provide “an inappropriate level of care” for some youth, which is why a detention center is badly needed.

At least one longtime advocate for incarcerated people agrees.

Richard Garland is desperate to keep kids out of adult prisons, which he said is where some will end up if they don’t receive services while they’re in the more rehabilitative juvenile justice system. There were 25 children in the Allegheny County Jail on Nov. 8.

Garland, the executive director of Reimagine Reentry, which provides services to formerly incarcerated people, said Adelphoi is a “tried and tested” provider of therapy and other supportive services. He described having good experiences with them that date back to the 1990s, when he first started his violence prevention work.

But he was alarmed by the allegations in the civil complaints, which PublicSource shared with him during a recent interview. “That sends up a real big red flag for me,” he said.

Adelphoi’s care for ‘vulnerable’ children questioned

Franchi’s client — anonymized as A.M.M. in the civil complaint — was a child in the Bradford County foster care system when he encountered Dunn, an Adelphoi in-home worker at the time. The complaint alleges she groomed him via phone messages and during trips to his foster home. She was soon barred from contacting him by a Protection From Abuse order.

“Adelphoi knew or should have known that Dunn had inappropriate contact” with the minor, according to the complaint, and the firm “did not take steps to intervene or protect” him.

The complaint says she eventually kidnapped him, withheld food and water from him, and repeatedly sexually and physically abused him. When Dunn let him drive, it alleges, he sped on a highway to try to get pulled over by police, leading to Dunn’s arrest.

Dunn’s attorney didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The suit seeks damages from Bradford County, a county caseworker and Adelphoi Services for being “indifferent to the risk of sexual victimization to children in county custody.”

Pratt said Adelphoi reported the abuse to state police and ChildLine, and was “wholly supportive of the legal process and consequences” imposed in the criminal case.

The separate class-action lawsuit alleges a longstanding pattern of “negligent staffing” and cases of abuse dating to 1998. The class of the suit includes current or former residents of any Adelphoi juvenile facility who “were subjected to either physical, mental, and/or sexual abuse by any [Adelphoi] staff members … and/or either had their educational opportunities deprived,” according to the complaint.

It accuses Adelphoi USA, the parent organization, of failing to properly screen, train and supervise its employees, some of whom sexually and physically abused the plaintiffs. “Many of the children who were abused at Adelphoi USA were vulnerable, intellectually disabled, and already fleeing from abuse,” according to the complaint. The nonprofit’s staff “took advantage of children who had already been victims of sexual abuse and were at Adelphoi USA to seek healing.”

The complaint alleges Adelphoi USA also misrepresented the abuse as part of plaintiffs’ treatment. The abuse often took place during “therapeutic sessions,” which made the plaintiffs believe it was “normal” and “medically necessary,” the complaint says.

The complaint argues that attempts to deceive plaintiffs toll the statute of limitations to file claims for physical and sexual abuse.

It was “almost impossible” for children to stop the abuse or get help because Adelphoi USA limited their phone usage and cut off their contact with the outside world, according to the complaint.

“Many of the children who were abused at Adelphoi USA were vulnerable, intellectually disabled, and already fleeing from abuse.”Complaint in ADAMS, ET AL. VS. ADELPHOI USA

Some amount of violence and abuse “is almost inevitable when you lock people up,” said Sara Goodkind, a professor at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Social Work. She added that some facilities are better-managed than others.

“We’ve heard really concerning things about Adelphoi,” said Jessica Feierman, senior managing director of the Juvenile Law Center in Philadelphia. But “those kinds of stories” aren’t unique to them and happen in public and private facilities across the state and country.

How will Adelphoi operate Shuman?

Shuman has a long history of failing to protect young people from harm, according to a report, co-authored by Goodkind, that explored ways to end youth incarceration in the county after Shuman closed.

The researchers interviewed young people — ranging in age from 14 to 27 — who were held at Shuman. They described moldy food, inadequate medical care and unsanitary conditions there. Many said staffers were abusive and predatory, though a few were helpful and supportive. One described Shuman as a place that “grooms kids for crime, not healing.”

PublicSource asked Adelphoi if it believes it can do better.

Pratt said Adelphoi “maintains the highest standards of care” across all its programs, including detention. Its management of Shuman will be trauma-informed, she said, though she didn’t specify what that will look like.

Adelphoi will bring in UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh to provide nursing care and manage medication, which is a condition of its contract with the county. Medication errors were among the violations that led to the revocation of Shuman’s license.

The lawsuits raise questions about how Adelphoi will screen candidates for jobs at Shuman.

Pratt said Adelphoi has already begun interviewing candidates for 25 open positions at Shuman. They’ll be screened via child abuse and criminal history checks, and their fingerprints will be run through the FBI database.

She didn’t answer a question about how much Adelphoi will pay workers at all levels at Shuman, though she said wages would be competitive in the local market.

Goodkind said the least qualified and trained workers in a detention center tend to work undesirable shifts and often aren’t paid “more than you might get … for working at Target.” While all staff are capable of abuse, the risks are elevated with low-paid, undertrained “line staff,” she said.

Adelphoi faced a labor shortage during the COVID-19 pandemic that forced it to scale back services and ask staff to work overtime, according to its most recent annual report.

A civil complaint filed last year in the Westmoreland County Court of Common Pleas by plaintiff Timothy Rice alleges that insufficient staffing contributed to Adelphoi’s failure to protect him from a stabbing attack by three other residents when he was placed at Adelphoi Village in Latrobe.

“At the time of the stabbing, it is believed there was only one member on staff in the facility which is against standard policy,” said the complaint.

The complaint alleges that proper Adelphoi policy requires at least two staff members to be on duty at all times to ensure the safety of residents. It also alleges that failures, including understaffing, allowed Rice’s attackers to possess a weapon despite one of them having a known violent past, and slowed the response to the attack.

Rice’s attorney, Daniel Soom, declined to comment.

Pratt said Adelphoi’s staffing issues have eased; it has seen a 65% decrease in open positions over the past four months.

The county is paying Adelphoi a flat fee of $7,800 per day for 12 beds, with the goal of expanding to 60 beds for $39,000 per day. Pratt said that should reassure community members who are concerned about incentives for “maximizing the number of youth in the program.”

Incentives to fill beds have backfired before in Pennsylvania: Luzerne County judges sent children to for-profit jails in exchange for kickbacks in the notorious “Kids for Cash” scandal, which didn’t involve Adelphoi.

While a flat fee is good, it could still incentivize judges and other stakeholders to send more kids to Shuman, said Jeffrey Shook, a professor at Pitt’s School of Social Work.

They could say, “We’re paying for it, we’ve got to move kids into this system,” he said, warning that “the deeper kids get into a system, the more likely they are to stay in a system and go into the adult system.”

Goodkind said it’s important to understand that detention facilities typically house young people for short periods of time before they’re adjudicated or found delinquent. That means many will be held at Shuman before it’s been determined that they’re guilty of an offense.

She added it’s a common misconception in the community, and even among some political candidates, that detention centers provide long-term rehabilitative services. The average stay at Shuman was around 12 days when it closed, according to the county.

Pratt said Adelphoi’s goal is to “minimize as much as possible” the amount of time youth spend in detention. That way, they’ll be placed into treatment plans that “most align with their unique needs.”

But Long isn’t buying it.

No matter how private detention contractors market themselves, she believes they will always “default” to a carceral approach. If they really wanted to help kids, they would do it “without the requirement of incarceration.”

Harris said he recidivated after his time at Shuman because he was sent back to his traumatic home life with no support. He’d like to see a program for incarcerated youth “whose goal is to put themselves out of business.” If the county tried hard enough, it could work toward that goal, he said.

“But a corporation can’t have it because they’re trying to make money.”

Correction: The complaint filed by A.M.M. names as defendants Adelphoi Services Inc., Bradford County and a county caseworker. An editing error in an earlier version of this story indicated another defendant.

Venuri Siriwardane is PublicSource’s health and mental health reporter. She can be reached at venuri@publicsource.org.

Tanya Babbar is an editorial intern at PublicSource and a junior at the University of Pittsburgh. She can be reached at tanya@publicsource.org.

Charlie Wolfson contributed.

This story was fact-checked by Jack Troy.

This reporting has been made possible through the Staunton Farm Mental Health Reporting Fellowship and the Jewish Healthcare Foundation.

Adelphoi’s pledges

Key points in the nonprofit firm’s role with, and promise to, Allegheny County, expressed in its contract and in responses to questions from PublicSource:

- Adelphoi said it has an “impeccable” licensing history with the Pennsylvania Department of Education and Department of Human Services. It’s accredited by The Joint Commission, the nation’s oldest and largest independent healthcare accreditor.

- About 79% of youth placed at Adelphoi facilities completed its programs in 2022 and 80% remained out of care one year after they were discharged.

- Adelphoi said it will provide youth held at Shuman with education, medical and dental care, mental health services, recreational opportunities and spirituality services.

- Adelphoi’s contract with the county allows it to use “physical techniques” to manage crises at Shuman. Staff are trained to use “alternatives to restraint” first, but will use “passive restraint” in situations that pose “imminent danger to oneself or others,” according to Karyn Pratt, Adelphoi’s vice president of marketing and strategy development. All restraints are recorded via camera systems and reported to the placing agency.

- Adelphoi will influence how courts and probation officers make decisions about youth in the criminal justice system. It will provide those stakeholders with a “high-level view of all clinical and assessment information” about a child. It will also provide that information to the treatment provider that a court or probation office selects for that child.

- Elizabeth Miller is Adelphoi’s medical director and is responsible for clinical practice and overall care at Adelphoi facilities. She is a professor of pediatrics at the University of Pittsburgh’s School of Medicine, and is chief of the Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.