Unbalanced

How property tax assessments create winners and losers

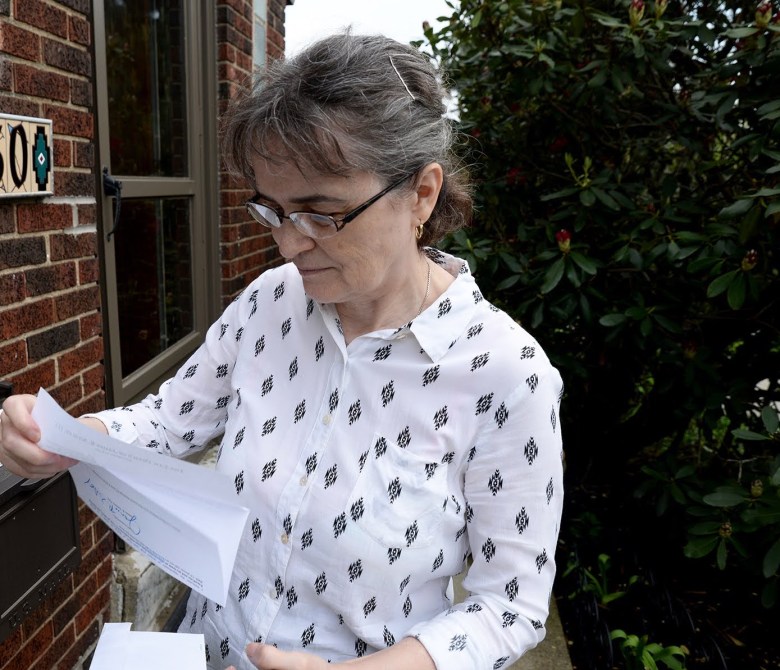

Flavia Laun visited at least 50 houses before she found one that fit both her lifestyle and her budget — or so she thought. Until the letter came.

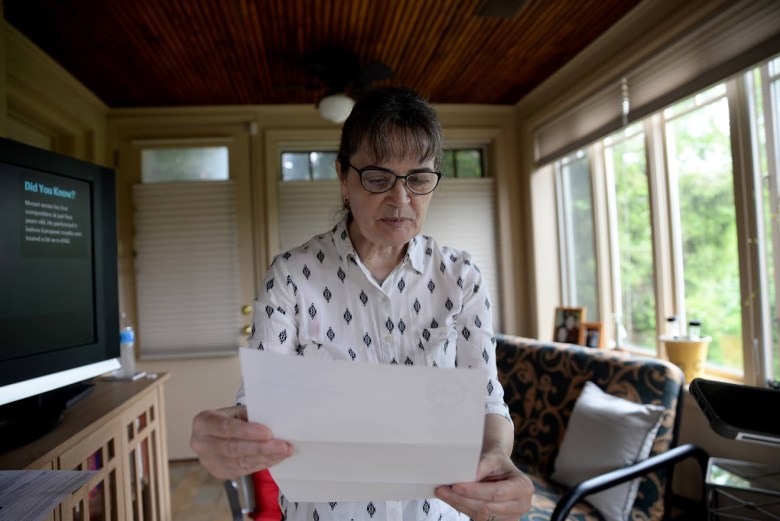

In the spacious sunroom behind the rhododendron on a May afternoon, she brought out the piece of Woodland Hills School District letterhead she received the month before. “Dear taxpayer,” it began, before telling her that the property tax assessment on her house is being appealed.

It was followed closely by a stream of letters from attorneys eager to represent her. She called a few, but didn’t hire any.

“I’m going to lose no matter what,” said Laun, 61. That could mean a hike in her total property tax bill of more than $2,500. “Shall I lose an extra $1,000 paying an attorney?”

Instead, she was trying to gather the information needed to represent herself – though the effort seemed to be affecting her fragile health. “Physically, I’m exhausted. And mentally, too, of course,” she said, blaming “this whole process of the assessment taxes, the way they’re calculated, and the faulty math and lack of logic.”

She knew from experience that it doesn’t have to be this way.

This year, assessment appeals — filed mostly by school districts, but also by some municipalities — are complicating the lives of around 10,000 residential property owners in Allegheny County. School leaders say those appeals are a way to raise much-needed revenue in a county in which assessments otherwise remain flat. Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald has opted since 2013 not to attempt to reassess all properties regularly, but instead to use values from 2012 indefinitely, except where they are altered by appeals.

Fitzgerald in an interview called the district appeals “totally unfair.”

The county’s property tax regime would be illegal in 38 states, which require regular reassessments of all property. It is also notably different from the policy in Philadelphia, which is the state’s most populous county and city. There, a new computer-assisted assessment system and enhanced homeowner protections are setting the stage for annual adjustment of tax bills.

While property assessment isn’t an exact science, tax bills can and should come reasonably close to reflecting market realities, said Randall Walsh, a University of Pittsburgh economics professor who has researched on housing markets. “You just need to get away from what is, to be frank, an antiquated approach to doing this,” he added. “It’s the refusal to update those assessments every year, or every other year, that’s the problem.”

‘Come back home’

Raised in Romania, Laun married a southwestern Pennsylvanian, spent two decades working as a programmer for the University of Pittsburgh and found a home in Edgewood. She divorced, and her son and daughter attended Woodland Hills schools before she moved to a Denver suburb.

She bought a Colorado condo in 2011, but never felt welcome. In March 2021, she talked with a former Pitt colleague who said three words – “Come back home” – that resonated. Three months later, she moved back and started house hunting.

The house market was hot, and she spent $225,000 — the proceeds from the sale of her condo, plus more — on a house in Churchill.

“Nobody even wanted to talk about taxes,” Laun recounted. “Every time I asked questions about property taxes, the only thing I heard from my Realtors was, ‘You know you’re going to Allegheny County where the taxes are high.’”

She was led to believe that the tax bills on her Churchill home would total somewhere shy of $5,000.

Now she’s worried that they will be much higher.

Need a brief primer on property taxes? Click here.

Equity ‘blown apart’

Colorado is among 38 states that require regular reassessment of property, according to a tally by the International Association of Assessing Officers [IAAO]. Most of those require reassessments every one, two or three years, though a few allow gaps of as long as six years or more.

Pennsylvania, by contrast, requires that counties assess property, but gives them the option of sticking with values set in a “base year” indefinitely.

In Allegheny County, decisions on reassessment have been driven by judges and local politicians. A series of court cases alleging unfair property taxes spurred repeat reassessments from 2001 through 2012. One casualty: the political career of the county’s first executive, Jim Roddey, who lost a 2003 election focused on the reassessment’s effects on property taxes.

After Roddey lost, no other politician would willingly brave a full reassessment, said state Sen. Wayne Fontana, D-Brookline, who was a county councilman at the time.

About Unbalanced: This year, PublicSource is exploring the effects of property taxes on people and communities a decade after Allegheny County’s last reassessment.

Fitzgerald ran on an anti-reassessment platform, and other than reluctantly implementing a court-ordered set of property values for 2013, he has kept his promise.

Stable assessments have “led to an awful lot of property values going up in Allegheny County,” Fitzgerald said in an interview with PublicSource. He touted the county’s homestead tax exemption under which the first $18,000 of an owner-occupied home’s assessment isn’t taxed by the county as a boon to owners with lower values.

While Fitzgerald said he favored statewide tax reform that would reduce schools’ reliance on tax reform, he believes the base-year system should continue in the absence of that. “In some counties, it’s lasted for more than half a century,” he said.

An analysis by the Allegheny Institute think tank indicates that nine Pennsylvania counties last reassessed prior to 1973.

Fitzgerald’s decision not to reassess, though, has had consequences for taxpayers and communities. In the series Unbalanced, PublicSource has reported that:

- Tax values have been outstripped by market prices, and hungry taxing bodies have appealed the assessments of homebuyers, creating wildly different tax bills for similar houses.

- A court challenge to the data used to calculate assessments after appeals has revealed that a key factor in the formula was inflated, resulting in higher tax bills for thousands of property owners.

- With most residential assessments still frozen, 30 of the county’s 130 municipalities have seen their property tax bases erode since 2014, compelling some to raise taxes or cut services.

- Because homes in lower-income areas have appreciated less, the levy has become regressive, with Black homeowners in Pittsburgh paying property taxes at an estimated 7% to 8% higher rate, relative to the market value of their homes, than typical white homeowners.

Delay in reassessing “creates inequalities over time,” said Larry Clark, the IAAO’s director of strategic initiatives. “You may have a market that generally is increasing, but then parts of it are increasing at different rates, and so over time the equity that we’re trying to achieve through the assessment process is blown apart.”

‘Absolutely outrageous’

Laun found more problems with her home than she had anticipated. Faulty downspouts, leaks, cracks and broken appliances ate at her savings and her income from Social Security Disability.

Then the letter from the school district arrived. She began researching, reading, calculating, talking with friends. She looked at sale prices and assessments in her neighborhood.

The house next door to Laun’s is around the same age, with around 16% less living area but nearly 50% more yard.

Laun’s total tax bill, though, is around 48% ($1,300) higher than her neighbor’s — and likely to go up from there.

She has studied the formula that determines property tax appeal decisions, which are based on the sale prices modified downward to approximate 2012 values. That formula is likely to change due to a lawsuit alleging that it is based on flawed data that the county submitted to the state.

The appeal could boost Laun’s total property tax to a level more than double that of her neighbor. She called the potential tax bill of nearly $7,000 “absolutely outrageous.”

‘Everybody looks at me like I’m nuts’

Filing assessment appeals is the least bad option available to schools, said Woodland Hills Superintendent Dan Castagna.

“We have to generate revenue to support a district operation that can work outside of the typical raising taxes and reducing staff,” he said. He’d rather see the state fund schools fairly but, barring that, he said the “fairest approach” is to file appeals when sale prices far outstrip assessments.

“School districts can’t keep up” with rising costs, said Ira Weiss, solicitor for the Pittsburgh Public Schools. “The taxing bodies are forced to exercise their rights under the assessment laws and file appeals,” he said. “It’s the only tool they have.”

Fitzgerald disagreed, pointing to districts’ ability to raise the millage rates, which would change tax bills for all property owners in the given district. “And they’ve got other revenue sources they can use.” Instead, he said, districts “pick on one newcomer, moving in, an unsuspecting newcomer in some cases … and then boom, they get smacked” with an appeal.

It’s a tactic that some would like to wrest from the districts’ hands.

“I literally can’t go to a Cub Scout meeting or buy a hot dog anywhere without someone complaining to me about school district taxes and how unfair they are,” said state Sen. David Argall, R-Schuylkill. “If you have 10 identical houses on one block, and nine are paying one rate, and one is paying another rate, how can that be fair?”

Argall has proposed a bill to bar districts from appealing based on the sale prices of homes, a practice sometimes referred to as spot assessment. It’s now before the Senate Urban Affairs and Housing Committee.

Two Senate Democrats said they oppose Argall’s bill.

“I feel for any taxpayer that gets that spot assessment,” said Sen. Lindsey Williams, D-West View. “But we need a broader overhaul of our tax assessment process,” including regular reassessments, she said. In the meantime, she said, removing their right to appeal is “untenable for their financial situation.”

“The perception out there is that if you do a reassessment, everybody’s taxes will go up. We know that’s not necessarily true,” said Fontana, who is both a legislator and Realtor. Anti-windfall laws would force taxing bodies to adjust millage rates, allowing some tax bills to rise, but pushing others down.

Still, when he suggests mandatory reassessment to his colleagues in Harrisburg, “Everybody looks at me like I’m nuts,” he said. “… Anybody that’s elected, they’re afraid they’re going to get tagged with [ads that say] you want to raise property taxes.”

Fitzgerald noted that his job will be on the ballot next year, and county term limits prevent him from running again.

“Candidates can obviously campaign on reassessing everybody’s property in Allegheny County,” he said, wryly. “I think there’ll be other issues that people can campaign on.”

Argall said he’d really prefer to get rid of property taxes.

He has unsuccessfully pushed bills that would replace school property taxes with other levies, arguing that “there has to be a better way to fund our public schools than: how big is your house, how many acres is it on, what color is your roof.”

Replacing the property tax, though, wouldn’t be simple.

An analysis by the state’s Independent Fiscal Office, released in April, found that to replace the property taxes now collected by schools, the state would need to combine a 2-percentage-point increase in the sales tax, a boost in the personal income tax of 1.85 percentage points and a 4.92% tax on retirement income except Social Security.

Funding education with property taxes, said Weiss, “is not a perfect system, but no one’s come up with anything better.”

‘Standing still just makes things worse’

According to a tally maintained by the Allegheny Institute, 53 of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties tax property based on assessed values that are even older than those used in Allegheny. But the state’s biggest city is not among them.

Philadelphia reassessed property in 2020. Last month, the city/county administration released fresh values for all properties within its borders, along with a series of measures to cushion the blow on any homeowner whose value is rising steeply.

Philadelphia generated the new values using a Computer-Assisted Mass Appraisal [CAMA] that is different from the personnel-heavy process of the past.

“In the old days, when I began, we would go from property to property and record the characteristics,” said the IAAO’s Clark, who served as a consultant to Philadelphia’s process. “Then we would go back to the office and look up specific characteristics in some manual” and piece together a value based on the house’s features and the sale prices of similar structures.

CAMA automates all of that, said Clark.

To implement CAMA, Philadelphia — which includes virtually the same number of property parcels as Allegheny County — hired a vendor for $14.8 million, payable over eight years. Armed with the system, Philadelphia’s Office of Property Assessment found that the total market value of properties within its borders rose by around 21% since 2020.

That won’t, however, mean 21% tax hikes for most homeowners. Mayor Jim Kenney’s administration in May announced measures that it said would put much of the new revenue “back into the hands of taxpayers,” as it pledged in a press release. The administration plans to:

- Reduce the city’s wage tax

- Raise the homestead tax exemption from $45,000 to $65,000

- Increase funding to a Longtime Owner Occupants Program, which allows owners who have lived in their homes for 10 years or more to blunt assessment increases

- Increase marketing of its Senior Citizen Tax Freeze Program.

With the computers and protections in place, the city plans to reassess every year.

Fitzgerald said he has not studied Philadelphia’s process, but said the money Allegheny County could spend on a reassessment would be better used for infrastructure or workforce development initiatives.

Allegheny County can’t just copy Philadelphia’s solution, said Michael Lamb, the controller for the City of Pittsburgh and the Pittsburgh Public Schools.

While Philadelphia is a unified city, county and school district, Allegheny includes 130 municipalities and 43 school districts. Even if the county boosted its homestead exemption, that would not apply to municipal and school taxes, which are often higher.

Instead, Lamb said, the county could consider assessing homes on a different scale than other properties. Or it could limit increases in assessments on homes at “a certain percentage above their current assessment.” He added that he did not know whether those measures would run afoul of the state Constitution’s requirement of uniform taxation.

In California, when a property is sold at a market price, that price becomes its new tax assessment. Each year thereafter, the property’s assessment increases by either 2% or the rate of inflation – whichever is lower – until it is sold again.

“That kind of model can work for us,” said Lamb. But right now, the county is abdicating its responsibility to assess fairly, he added. “Standing still just makes things worse and that’s what we’re doing right now.”

‘I am alone in this’

Laun continued to research the sale prices of comparable properties in preparation for her late June telephone hearing before the Board of Property Assessment Appeals & Review. The letters from attorneys were still coming, and Laun’s son was encouraging her to fight. But she despaired of her chances and craved clarity.

“I want to see the bill,” she said. She figured her remaining savings could cover the first year’s property tax payment, and then when she turned 62 she could pay her next bill through an early withdrawal from her retirement account.

She would likely make it through. But a year after she returned to Allegheny County in search of community – to “come back home” – she felt anything but settled.

“I am all alone in this,” she said, “although there are many people in my situation.”

Rich Lord is PublicSource’s managing editor. He can be reached at rich@publicsource.org or on Twitter @richelord.

This story was fact-checked by Terryaun Bell.

How property taxes work

Property taxes cover the biggest share of the cost of local government and are supposed to be related to the values of taxable land and buildings. In Pennsylvania, counties have the job of estimating the fair market values of taxable properties.

State law allows counties, municipalities and school districts to abate some portion of that value for homeowners, seniors, farmers and a few other categories of owners. Allegheny County, its school districts and some municipalities including Pittsburgh have various abatements for homeowners. The county, for instance, doesn’t count the first $18,000 in a homeowner’s fair market value when calculating the tax due.

The taxing bodies must then multiply the remaining values by their tax rates — referred to as millage — to get the tax bill.

(Fair market value – abatements) x the millage rate / 1,000 = property tax

In 2012, Allegheny County Executive Rich Fitzgerald decided to keep using that year’s property value assessments indefinitely, rather than continue a series of contentious mass reassessments. That effectively froze the assessments of property owners who don’t move or make major changes to their buildings.

Property owners, though, may appeal their own assessments, and school districts and municipalities can challenge the valuations of any property within their borders. Taxing bodies often file appeals when a property sells for a price that’s far higher than its assessed value, arguing that the sale proves the fair market value.

The Property Assessment Appeals and Review Board then decides whether the appeal is valid. It applies a new assessment, often based on the sale prices modified by a Common Level Ratio meant to approximate 2012 values.