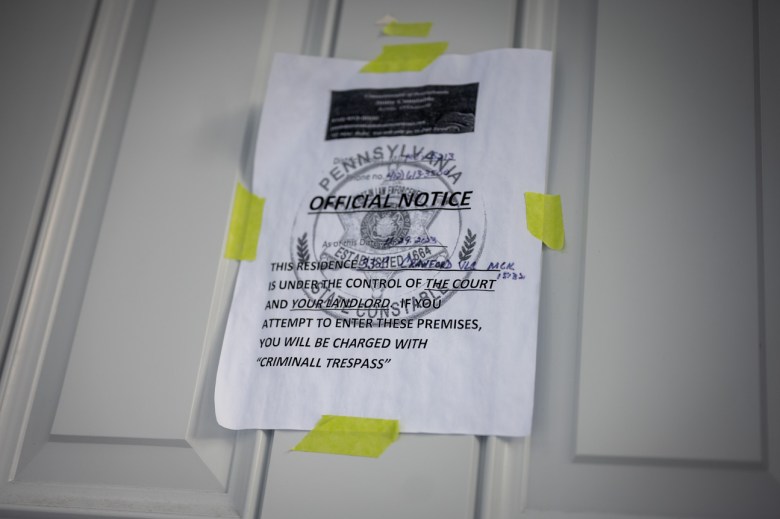

On a Tuesday afternoon in December, around a dozen public housing tenants facing eviction filled a waiting room in McKeesport, where Magisterial District Judge Eugene Riazzi asked each if they could pay their delinquent rent.

If so, the tenant agreed to pay the amount owed, plus court costs of more than $150. Unless they pledged to pay, Riazzi ruled in favor of the McKeesport Housing Authority, starting a process that can lead to the tenant’s removal within weeks. Tenants who said they couldn’t pay were referred to a county human services worker who waited in the lobby to help them apply for rental assistance.

A similar scene plays out on many Tuesdays in McKeesport.

Since the end of the pandemic-era moratorium on evictions in 2021, all three housing authorities serving Allegheny County have filed numerous eviction cases, but none has done so with the same vigor and frequency as the McKeesport Housing Authority [MHA]. These legal actions come as county human service officials and advocates cement a rental assistance network created through pandemic-era federal funding that’s helping tenants of the Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh and the Allegheny County Housing Authority.

The McKeesport authority, by far the smallest of the three agencies with the fewest number of housing units, has filed 562 landlord/tenant cases against its tenants from the start of 2021 through early December. Pandemic-driven curbs on most evictions ended in 2021.

The Allegheny County Housing Authority [ACHA] filed 131 cases and the Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh [HACP] filed 263 in that same time period, according to court data gathered by Anne Wright of Carnegie Mellon University’s CREATE Lab, who tracks eviction cases.

Wright noted that tracking eviction filings for Pittsburgh’s housing authority can be difficult because the organization often uses various names when filing evictions against tenants. Eviction filings also do not necessarily correlate with actual evictions, as some tenants are able to gather the money and stay after a filing.

McKeesport Housing Authority solicitor Jim Creenan wrote in response to questions that the three housing authorities are structurally different. The MHA, he said, has limited resources, so it needs a consistent stream of federally required rent from tenants. He also noted that the authority has a “substantial waiting list” of families wanting to move into its communities.

Pittsburgh’s and Allegheny County’s housing authorities also have waiting lists for the units they manage.

County human service officials said that the Pittsburgh and county housing authorities are using partners including Just Mediation Pittsburgh to prevent evictions, while MHA has largely declined to use these resources.

From poor white roots to intersectional anti-poverty solutions for all

“Prior to the pandemic, the largest filers of evictions were the housing authorities, and at least two of the three housing authorities here are using mediation as a first step to avoid evictions. So that drastically reduced the number of filings we’ve seen in the county,” said Chuck Keenan, an administrator of the Office of Community Services within the Allegheny County Department of Human Services [ACDHS].

Keenan said the MHA used the county’s eviction prevention services at the beginning of 2023 to mediate around 20 tenant cases. Keenan said the housing authority has since stopped using mediation and returned to filing evictions against their tenants.

“They’re not really using mediation as much as we would hope,” he said. “We would encourage all landlords to use mediation as an alternative to filing — including the housing authorities.”

McKeesport’s Creenan said the authority “has entered payment plans and we have facilitated hundreds of applications for each stage of the COVID-era rental assistance.” In most cases, those tenants continued to rack up delinquencies, he said.

He added that each mediation requires hours of staff time and the resulting delays in payment did not “align with our limited resources and contributed to the arrears” owed the authority.

Fewest units, most landlord/tenant cases

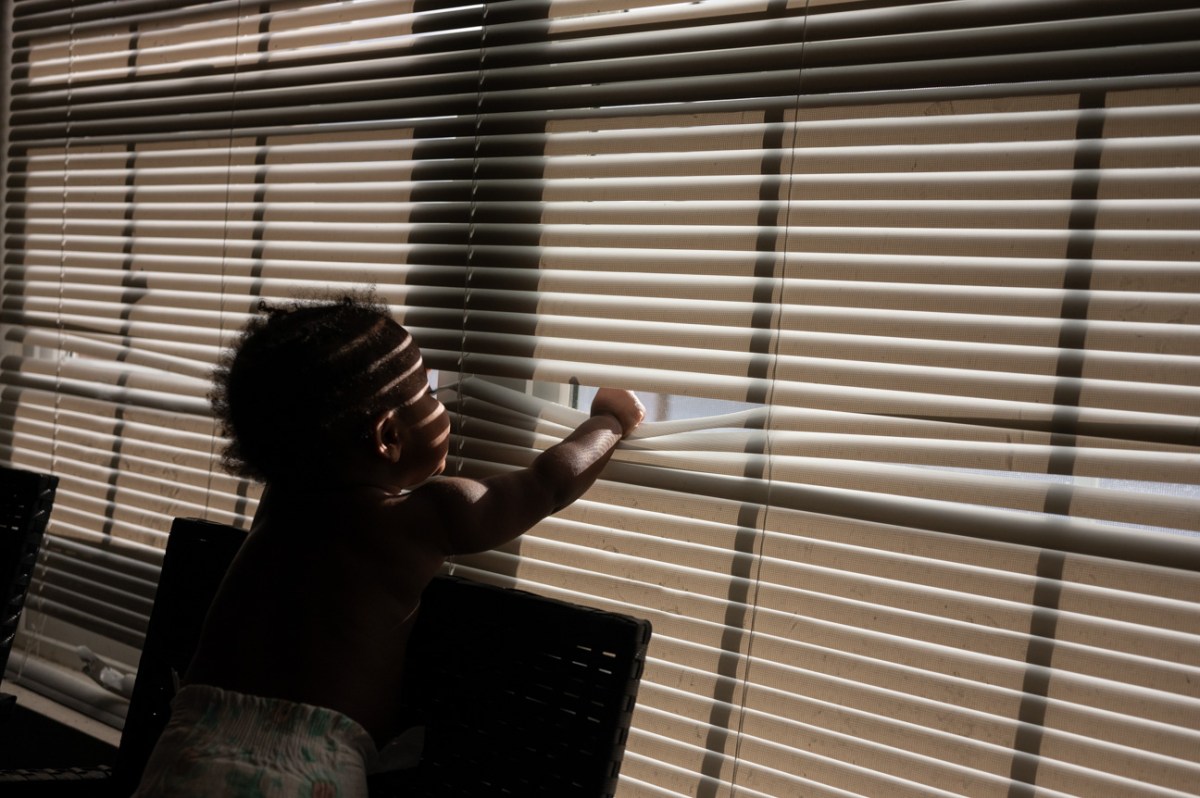

Ziara Wright, a mother of two in McKeesport who is facing eviction and owes several months of rent, said she was still making partial rent payments last year before the housing authority took her to court. She fell behind in part because of a paperwork problem that led to her losing access to her food stamps, forcing her to spend more money to feed her family.

After a ruling against her and a judgment of $2,417, she filed an appeal. The eviction process and filing for an appeal has been stressful, she said.

“You got to go through that while you’re juggling everything else. You got to pay your bills out there. You got to go to work every day,” she said.

Speaking broadly, Creenan said that with all of the protections afforded to tenants — including appeal rights and rental assistance — only about 20% of the first-time evictions the authority files against tenants lead to a judge’s order for possession, entitling the authority to remove the tenant.

“Many tenants appear to be gaming the system,” he said, “as the number of tenants filing late appeals and other delay-type motions to the Court of Common Pleas have increased dramatically in the past two years.”

Local housing advocates urge inexpensive mediation before court filings. Landlord/tenant complaints result in fees and legal stains that can hurt the tenant’s ability to find rental housing in the future.

The McKeesport Housing Authority has 1,021 housing units, and last year it filed a landlord/tenant case for roughly 1 out of every 4 of its housing units. In contrast, the Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh brought cases against around 4.6% of its tenants, or about 1 in 20. The county’s housing authority, with 3,839 units, filed cases against 2.6% of its tenants last year.

Uptown residential development seeks to adorn generic design with ‘museum-quality’ art

MHA’s Executive Director Steve Bucklew declined to discuss its eviction policies with PublicSource and WESA, citing unspecified, ongoing litigation. He referred reporters to a published report by the Public Housing Authorities Directors Association, citing ongoing rent collection difficulties for housing authorities.

In an interview with PublicSource in 2022, with pandemic-era rental aid expiring, Bucklew said too many tenants were delinquent in their rent.

“We’ve never experienced delinquencies like this,” he said at the time. “There’s groups trying to delay evictions, but I feel that the only way the message will be communicated to tenants that they have to pay rent is by filing evictions.”

Pittsburgh and Allegheny leaning against eviction

The county Department of Human Services has been working with ACTION-Housing, Rent Help PGH and Just Mediation, among others, to divert landlord/tenant disputes to mediation, rather than court.

The county and those agencies have learned a lot since 2021, when pandemic-driven rental assistance started, said Keenan. He said the county in 2023 provided rental assistance to more than 1,100 households, totaling upward of $14 million, whereas pre-pandemic spending was $2 million to $3 million a year.

Pittsburgh and Allegheny County’s housing authorities try to avoid court.

“Eviction prevention has become a standard operating procedure for the Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh,” said Anthony Ceoffe, senior director of asset management for HACP.

Ceoffe said HACP worked with Just Mediation Pittsburgh and Rent Help Pittsburgh to help mediate cases with its tenants who are facing problems paying their rent. As a result, he said, the authority didn’t evict any tenants in 2023 because of nonpayment of rent. (Some evictions did take place for issues including safety violations, he said.)

Ceoffe said the authority also has used a partnership with a third party to connect its tenants to budgeting classes, financial literacy and ongoing case management.

“So just because somebody has received rental assistance, that does not mean that the eviction prevention coordinators are done with them,” Ceoffe said.

Landlords and tenants in mediation have access to available rental assistance — so landlords are still able to eventually get the funds owed to them.

HACP officials said the book “Evicted,” work by local foundations and advocates, and lessons from the pandemic have contributed to a shift away from eviction filings.

“We are in the business of providing housing,” said Michelle Sandidge, chief community affairs officer for HACP. “To evict a bunch of people just … adds to the homeless situation. That is not something that we’re trying to do.”

Rich Stephenson, chief operating officer for the Allegheny County Housing Authority, said the agency has invested money and time in preventing evictions through mediation and financial literacy classes for tenants.

“We try to identify the problem,” Stephenson said, “because if someone’s behind in their rent, there’s usually an underlying problem.”

Eric Jankiewicz is PublicSource’s economic development reporter, and can be reached at ericj@publicsource.org or on Twitter @ericjankiewicz.

Kate Giammarise is a reporter at 90.5 WESA, Pittsburgh’s NPR News Station, covering housing and social services.

This story was fact-checked by Rich Lord.