Update (9/1/22): Allegheny County Court of Common Pleas Judge Alan Hertzberg issued an order setting the Common Level Ratio at 63.53%, and ordering the county to “immediately” submit supporting data to the State Tax Equalization Board.

Unbalanced

How property tax assessments create winners and losers

Many Allegheny County property owners will get the opportunity to slash their real estate taxes. The open questions: By how much? And when?

A lawsuit pitting property owners and their advocates against the county and school districts appears to be winding down, bringing a change in how taxes are calculated after assessment appeals.

For taxpayers who appeal their assessments, the lawsuit is likely to result in tax bills roughly 20% lower than they would have been under the county’s prior tax math. For homeowners who appeal, potential reductions could be even steeper because they can also tap the homestead tax exemption.

That prospect could bring a flood of property tax appeals. “Everyone’s going to say: ‘What about me?’” predicted Michael Suley, a real estate consultant who led the county’s Office of Property Assessments from 2006 through 2012 and is working with the lawsuit’s plaintiff property owners.

For owners of large commercial properties, appeals could bring big savings. For taxing bodies, especially school districts, it could mean budgetary pitfalls.

The impact is “alarming. Do the math,” said attorney Ira Weiss, whose firm serves as solicitor for the Pittsburgh Public Schools [PPS] and five other districts within Allegheny County. PPS relies on property taxes for around $189 million this year, covering more than one-quarter of its budget.

Depending on how it’s implemented, the impending change in the county’s property tax math could start cutting into revenues this year or next.

Said Weiss: “And there is no local government – school district or municipality – that can cope with that.”

Challenging the ratio

The lawsuit’s lead plaintiff is Maddie Gioffre, a systems engineer living in Wilkinsburg, whose house’s assessment more than doubled after she moved to the borough and the school district appealed its value. Thirteen months after filing in the Allegheny County Court of Common Pleas, and following lengthy negotiations and orders by Judge Alan Hertzberg, many of its issues were resolved with a July 19 order he issued.

Understanding that order requires a sense of the basics of property taxation in Pennsylvania and Allegheny County. (If you already know what a Common Level Ratio is, click here to skip to the next section.)

Even as some lawmakers try to eliminate or curb property taxes, the levy remains the single largest source of revenue for many of the state’s local governments.

Counties assign tax values to properties. Some counties revise all property values regularly, but Allegheny County hasn’t done so in a decade. Counties, school districts and municipalities decide on property tax rates, referred to as millage.

A property’s value (minus any applicable break for homeowners, farmers and low-income seniors) times the millage rate, divided by 1,000, determines the tax bill.

About Unbalanced: This year, PublicSource is exploring the effects of property taxes on people and communities a decade after Allegheny County’s last reassessment.

The owner, the school district or the municipality can appeal the value.

When someone appeals, the Property Assessment Appeals & Review Board [BPAAR] decides on the fair market value of the building and land, based on evidence of the recent sales of comparable properties. To get the property assessment, BPAAR then multiplies that market value by a factor called the Common Level Ratio [CLR].

The CLR is intended to reduce the tax bill to an amount comparable to those of similar properties. In Allegheny County’s case most assessments stem from 2012 market conditions. The CLR is calculated by the State Tax Equalization Board [STEB], based on a representative sample of recent market-rate property sales provided by the county.

More sales data could shave tax bills

STEB calculated a CLR of 81.1% for this year’s appeals, meaning that 2012 values were deemed to be around 81.1% of current values. Therefore, to be fair, a property with a market value of $100,000 would pay taxes based on $81,100.

The plaintiffs, represented by attorney John Silvestri, allege that the county provided STEB with a skewed sample of 5,357 sales, resulting in an inflated CLR. Hertzberg’s order last month compelled the county to give STEB a new sample including purchase prices of 10,114 properties.

Suley expects that the new data will result in a revised CLR in the “ballpark” of 64% once STEB gets the new data and finishes its calculations.

For an owner-occupied house in Pittsburgh with a value, determined via appeal, of $200,000, the total school, city and county tax bill with the faulty 81.1% CLR would be around $3,200. At a CLR of 64%, it would be around $2,400, according to the city’s property tax calculator. Suburban and commercial property owners would see different levels of savings because of varied tax rates and exemptions.

All owners who choose to appeal will have one thing in common, said Suley: “Everything moving forward will favor the property owners.”

Just maybe not yet.

Reopen the window?

BPAAR accepted appeals starting Jan. 1 and ending March 31, long before the court had compelled the calculation of a new CLR. It received 12,659 appeals of which 89% were filed by school districts and 92% related to residential properties.

That represents just a tiny fraction of the roughly 580,000 parcels in the county.

Many of those appeals have been put on hold, said attorney David Montgomery, BPAAR’s solicitor. He said the school districts are waiting for the new CLR calculation. “If the CLR drops in a significant way, the school districts may reconsider whether the appeals that they’ve filed are beneficial,” he said.

Take, for instance, a house that is now assessed at $200,000, but recently sold for $300,000. An appeal under a CLR of 81.1% would likely yield an assessment of $243,300, and an increase in the taxes due to the schools, municipality and county. But an appeal and a CLR of 64% would result in an assessment of $192,000 – and lower tax bills.

While districts can withdraw their appeals if the lower CLR undercuts them, there’s as yet no mechanism for the owners of properties in the county to slash their bills this year. That’s because the window for appeals closed at the end of March.

“They should definitely open up the period again,” said John Petrack, executive vice president of the Realtors Association of Metropolitan Pittsburgh [RAMP], which has supported the lawsuit. He said Hertzberg could conceivably order a new appeal period.

Suley argues that County Executive Rich Fitzgerald and County Council “should open the window” and allow another round of appeals, this year.

A spokesperson for Fitzgerald’s office wrote in response to questions that the administration would abide by any orders from the court regarding appeals.

County Council President Pat Catena said it’s premature to comment on potential courses of action since the litigation continues. “As soon as we have a bit more clarity surrounding the court case I will be suggesting additional action to my colleagues on County Council to not only get to the bottom of the previous breakdown in process but also what is the fairest and most equitable way we move forward,” he wrote in response to questions.

Regardless of what happens this year, next year will bring another opportunity to appeal assessments. The CLR is expected to be 63.6% – unless litigation forces another recalculation.

This year or next, said Suley, the “historic drop in the ratio … will be a lightning bolt to the school districts and other taxing bodies.”

‘Many adverse consequences’

Weiss did not dispute the lightning bolt characterization.

“The implication of this for school districts – and municipalities really – is that this can result in local governments and school districts taking a hard look at programs and necessary capital improvements,” the PPS solicitor said.

He added that school districts factor property tax appeals into their budgets, assuming a given CLR. When those budgets are set in stone, only to have the assumptions change, “there are many adverse consequences” that can emerge.

The City of Pittsburgh’s 2022 operating budget includes $657 million in revenue of which the biggest component is $151 million in property taxes. A slew of appeals could whittle that down.

Mayor Ed Gainey’s administration is watching the litigation closely, according to Jake Pawlak, the city’s deputy mayor and director of its Office of Management and Budget. He said the city is preparing revenue estimates based on several possible scenarios, but isn’t panicking.

“Overall, while we are taking the potential impacts of this case seriously and are monitoring them closely, we believe the City’s financial situation is stable and are cautiously confident in our ability to absorb revenue reductions resulting from a round of appeals without any major disruptions,” he wrote in response to questions.

How-to sessions on the appeal system

Lawyers, public officials and larger property owners are all preparing for the emerging appeals landscape.

‘“There’s a lot of interest regarding the lawsuit regarding the Common Level Ratio that may give thousands of people reason to appeal their assessments,” said attorney Bob Peirce, whose firm handles many property tax cases. He is leading an Allegheny County Law Library educational session on assessment appeals, open to both lawyers and the general public, at 1 p.m. Aug. 15. (There’s limited space for in-person attendees, but also a virtual option, and there’s no cost to the general public.)

Joined by Montgomery, Peirce plans to talk through a process that, for a homeowner, would likely include:

- Finding properties in your general neighborhood that are comparable to yours and that sold recently for market prices, so you can approximate your market value

- Taking out the calculator and figuring out whether – given the CLR – an appeal that resulted in that market value would raise or lower your tax bill

- Considering whether it’s worth going the extra step of hiring an appraiser to professionally estimate the market value

- Deciding whether to hire an attorney – which might run $1,000 – or appeal on your own.

Peirce said people like him, who live in homes they bought before 2012, might not be able to use the new CLR to shave their tax bills, which are already based on decade-old values. But property owners who bought in more recent years and then saw their assessments increased may benefit from appealing.

Expect the law library’s event to be one of several efforts to educate the public about the changing process.

County Controller Corey O’Connor has announced that he will work with the Pittsburgh Community Reinvestment Group [PCRG] and RAMP to hold information sessions on the assessment appeal process. Dates have not been announced, but the sessions could start in September.

“Unfortunately, we have witnessed the inequities of the current assessment system play out in some of our neighborhoods,” said PCRG Director of Policy Chris Rosselot, in a press release.

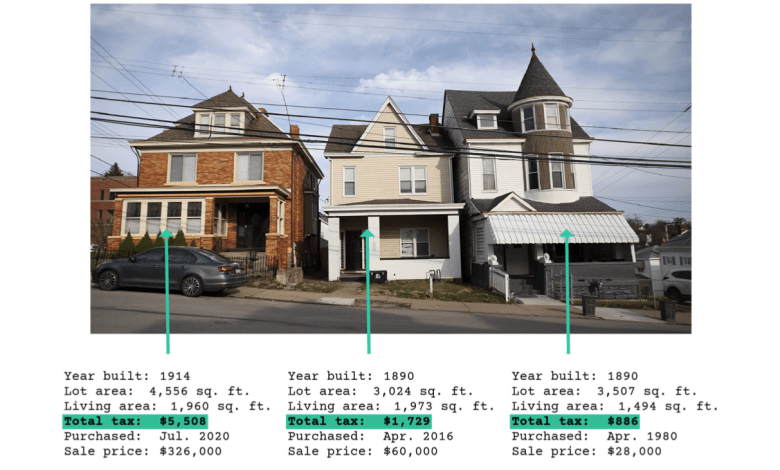

Those inequities, detailed by PublicSource in its Unbalanced series, stem from the sometimes-vast differences between the 2012 “base-year” assessments for some properties and much higher, appeal-driven assessments on others.

“The base year,” Suley said, “is a house of cards that is about to tumble.”

The Gioffre litigation makes no attempt to force the county to reassess all properties, nor does it seek what Suley called “reparations” for any taxes paid based on any inflation of the CLR in past years. He suggested, though, that the case, by undermining the county’s tax math, could set the stage for other challenges.

Petrack said there is now “a distinct possibility of a class-action suit” challenging the county’s CLR calculations and tax bills for several prior years.

He said the litigation has exposed, again, the shortcomings of the base-year tax system, and the need for regular reassessment of all properties.

RAMP has “advocated for a biennial or triennial reassessment for many, many years,” Petrack said. Compared to a system built on base-year values and appeals, regular, modest increases in property assessments are “much more palatable to the consumer and, coincidentally, much more budget-friendly to the taxing bodies,” he said. “It would be a win-win.”

Rich Lord is PublicSource’s managing editor. He can be reached at rich@publicsource.org or on Twitter @richelord.