Unbalanced

How property tax assessments create winners and losers

The accuracy and fairness of property assessments in Allegheny County are again being challenged in court. The legal wrangling is far from new. Current cases are just the latest iteration of property owners seeking judicial intervention because the county lacks any schedule to routinely reassess property values for tax purposes.

Today the county’s use of decade-old assessments to tax much of its property makes it an outlier. But there was a time when the county was almost in the vanguard of property tax sophistication — if only because judges compelled it to change.

Property assessments done by the county affect the taxes paid by owners to the county, municipalities and school districts.

Courts have had a direct role in managing assessments in the county at least since Green Tree sued over assessment practices in 1970. The lawsuit was just one manifestation of growing anger at the time over the accuracy and administration of property assessments in the county. In 1974, while the case lingered, the county commissioners appointed a committee to study the state of property assessments. Headed by county Solicitor Alex Jaffurs, the committee produced as comprehensive an evaluation of the county’s property assessment practices as has ever been written.

At the time, the county reassessed each property every three years, unlike today’s practice of base-year values altered by appeals. The committee report, though, identified a lack of uniformity in assessment practices. Individual assessors used their own methods and relied in part upon outdated Depression-era line drawings of properties.

About Unbalanced: This year, PublicSource is exploring the effects of property taxes on people and communities a decade after Allegheny County’s last reassessment.

In 1977, Wilkinsburg filed a lawsuit, which was consolidated with the lingering case brought by Green Tree and went before Court of Common Pleas Judge Nicholas Papadakos. He directed the end of the triennial assessment system in 1978 and then took the unprecedented step of certifying a consent decree that placed him in direct control of the county assessor’s office.

At the time, computer-assisted mass appraisal [CAMA] software was just beginning to emerge nationally. The Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, a Cambridge, Massachusetts, think tank, produced one of the first software packages for real estate assessment. That eventually resulted in software called SOLIR (Small On-Line Research), which ran on a common Radio Shack TRS-80 computer to assist property assessors.

Based on the recommendations of the Jaffurs committee report, Allegheny County issued a request for proposals [RFP] to find the best computer models to set property values. The county in 1978 gave seven firms a dataset with information on the characteristics of 3,500 recently sold properties, and the actual sales prices for only 2,800 of the transactions. The firms were evaluated on how accurately they estimated the sales prices of the remaining 700 properties.

The team that outperformed all others – including many long-established real estate firms – was made up of two local researchers who had developed a new computer model to predict property values. The team included Richard Longini, a professor of electrical engineering at Carnegie Mellon University with a secondary appointment at CMU’s School of Urban Affairs.

Longini had a Ph.D. in physics and a 28-year career in industrial electronic research before joining the faculty of Carnegie Tech — later CMU — in 1962. His previous research focused on quantum mechanics and the solid-state physics of transistors – the science that underlies all things digital in the modern world.

Longini’s curiosity over his home’s assessed value led him to expand his research portfolio far outside his background. I had the chance to meet with him in the 1990s, and he explained that he was not upset, but more confused by the valuation his Squirrel Hill home was given by county property assessors.

Longini and former CMU graduate student Robert Carbone, along with local real estate broker Ed Ivory, formed a software firm to apply the novel software to property assessments in Allegheny County.

The software they used was developed out of Carbone’s 1975 dissertation research. Carbone had queried the county on their assessment methodology. Unsurprisingly, the county’s response was unfulfilling and likely came nowhere near the rigor he applied in his engineering research.

How did Longini and Carbone outperform competitors in predicting sales values in the county? Early computer models used to set market values, such as the Lincoln Institute’s SOLIR, relied mostly on what is called multiple regression analysis. Regression is a standard statistical technique that can be used to break down individual property values into how much total value can be attributable to individual parcel characteristics including total size, the number of rooms and overall condition.

Longini and Carbone proposed a more sophisticated statistical technique using an adaptive estimation procedure [AEP] to predict real estate prices. Also called feedback models, AEP uses an algorithm that not only looks at the most recent sales data but evaluates historic data and errors in previous estimates to determine current real estate values. The technique was developed decades earlier but became more widely used after World War II in early rocketry and orbital mechanics, where it helped to track the movement of satellites and ballistic launch vehicles.

For Allegheny County, the software developed by Longini and Carbone proved faster and at least as accurate as the techniques used by other competitors in the 1978 RFP.

The county purchased the software Longini and Carbone had devised, but it would remain minimally used. Decades later, Longini told me that there was tremendous pushback from the staff of roughly 70 county assessors because of the threat it posed to their jobs. What need would there be for the services of so many assessors if a computer could quickly and presumably more consistently set assessment values?

New computer software was just one part of the modernization planned for the county assessment system. Though the county purchased the software implementing the feedback model, a full CAMA-based reassessment was not possible until core data was compiled for the roughly 580,000 individual property parcels, a huge task given that most data would need to be compiled from scratch. At the end of the 1970s, the county did not even maintain a common record card of information on individual parcels for use by its assessors.

Building the required database would be an enormous and costly task, and the bulk of the costs would have come due just as economic shocks were growing larger. The first of two back-to-back economic recessions began in January 1980 and had disproportionate impacts in Southwestern Pennsylvania, putting unprecedented stresses on public finances.

Due to the scale of the anticipated costs, pushback from county assessors or other reasons, the county never completed or consistently maintained a comprehensive database of real estate. Efforts at reforming assessments went into semi-permanent stasis once Judge Papadakos formally ended his oversight of the bureaucracy in 1982, before he was elected to the state Supreme Court in 1983.

Instead, Allegheny County mostly continued past assessment practices. Properties continued to be assessed by individual assessors, often with incomplete or out-of-date data. New lawsuits against the county were filed after newly elected county commissioners Larry Dunn and Bob Cranmer froze assessments and laid off all of the assessors in 1996. The cases were consolidated under Court of Common Pleas Judge Stanton Wettick.

Wettick ordered county assessments to restart, and a contract was awarded to Sabre Systems, an Ohio-based firm, to manage the system. Ironically, Sabre Systems was one of the firms evaluated by the county in the 1970s, only to lose the work to Longini and Carbone’s novel software. In 1998, Wettick went further and ordered the county to prepare to conduct its first comprehensive mass reassessment since the triennial system was in place decades earlier.

The county awarded a $24 million contract to Sabre Systems to complete the CAMA-based reassessment. Sabre managed the process of collecting data and building a database needed for CAMA models. It subcontracted the actual modeling of property values to EDA Feedback Inc., the firm that Richard Longini, Robert Carbone and Ed Ivory originally formed to implement CAMA modeling for Allegheny County in the 1970s. In effect, the county was paying for software it already owned.

When completed, new assessment values made public in 2000 were a shock to many property owners and were immediately challenged in court by new plaintiffs. Wettick directed that CONSAD, a local consulting firm based in East Liberty, evaluate the results of the reassessment and oversee a new mass reassessment to be completed for the following year. CONSAD’s report said the feedback model worked correctly but that Sabre Systems made several errors in applying the model.

One problem: The county had been divided up into too few subregions to properly calibrate the computer models.

CONSAD noted almost in passing what may have been a far more impactful decision by Sabre Systems. In calibrating its computer models, Sabre Systems did not use data on any property sales in which the transaction value was recorded as $10,000 or less.

Why was that decision fateful? One challenge in CAMA-based property assessment is determining what real estate transactions truly represent market values. In most markets, extremely low-valued real estate transfers are often not “arms-length” transactions, instead representing transfers between family members or other interested parties. But many local communities across Southwestern Pennsylvania had not experienced significant real estate appreciation in decades. As a result, many $10,000-or-under transactions in Allegheny County did indeed represent market values.

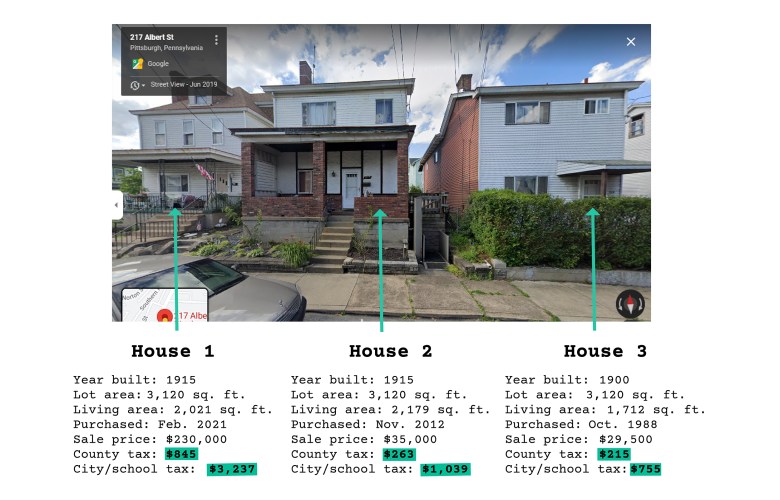

The blanket elimination of all sales values under $10,000 had a predictable result. Low-valued properties were systematically overassessed while high-valued properties were underassessed. Sabre Systems would not be retained for a follow-on reassessment that was completed by its competitor, CLT Systems.

The follow-on assessment of 2002 was completed for use with 2003 tax bills, but plans for a new reassessment every three years were later abandoned. More litigation emerged later in the decade, and the cases would again be consolidated before Wettick. His 2009 order forced the county to conduct a new mass reassessment. When finally completed in 2012, the county announced it would retain the 2012 values as its “base year” for assessments indefinitely into the future.

Which brings Allegheny County back to a familiar place. A full decade has passed since the most recent mass reassessment of property values and again, lawsuits are emerging challenging the accuracy and fairness of tax bills and the ongoing appeals process. What also remains the same is that the prospect of new property assessments remains a third rail of local politics, something to be avoided at all costs.

In a county with some history of regular re-evaluation of property tax values, which even spurred the development of industry-leading technology, there seems little prospect of systematic countywide assessment, something that is a common practice outside of Pennsylvania.

Christopher Briem is a regional economist with the Urban & Regional Analysis program at the University of Pittsburgh’s University Center for Social and Urban Research (UCSUR). He can be reached at cbriem@pitt.edu. This essay is an abridged version of a longer history of property assessment in Allegheny County available at briem.medium.com.