Falaknaz Paiwandi came to the Oakland Food Pantry in search of fresh vegetables and halal meat.

The 56-year-old father of four fled Afghanistan with his family after the Taliban seized power there in 2021. They left their home in Parwan — a rural province north of Kabul — for a New Jersey military base, where they joined thousands of Afghan refugees awaiting new lives in American cities.

They settled in Pittsburgh a few months later, but are finding it hard to afford food here. Paiwandi, a veteran of U.S.-backed Afghan armed forces, can’t work because he was injured in a car accident. His 23-year-old son, a laundromat worker, is the family’s sole earner. His wages are nowhere near enough to feed his parents and siblings.

“It’s too expensive and we’re not able to buy food for ourselves,” said Paiwandi, speaking in Dari through an interpreter. “That’s why we’re having a plan to get food from the food pantry.”

He selected apples, carrots, walnuts and mangoes, among other produce items. But he couldn’t have his pick of protein: There was no halal beef or chicken that day, so he took the salmon that pantry staff offered him.

About 30 Afghan families visit the pantry each month, according to Community Human Services [CHS], the nonprofit that runs it and offers other supportive services. Their needs highlight gaps in Pittsburgh’s charitable food system, which is struggling to keep pace with high demand and changing demographics in the region. Staff at food banks and pantries say more people with limited English proficiency are seeking food assistance. And few pantries offer halal meat — a crucial macronutrient for Paiwandi and other followers of Islamic dietary law.

CHS is trying to fill those gaps. It uses interpreters to communicate with people facing language barriers. It stocks the kind of fresh produce and grains that are staple foods in many countries. And it offers halal meat as much as its budget allows.

Staff said their efforts drew more refugees and immigrants to the pantry. High food prices and the end of pandemic-era food benefits are driving demand, too. Nearly 2,800 people used the pantry in the last fiscal year — a 77% increase from fiscal year 2022 that brought more traffic to the neighborhood and generated backlash from residents.

“We’re trying to be really good neighbors while also serving the community,” said Chief Executive Alicia Romano. “It’s been a really tough balance.”

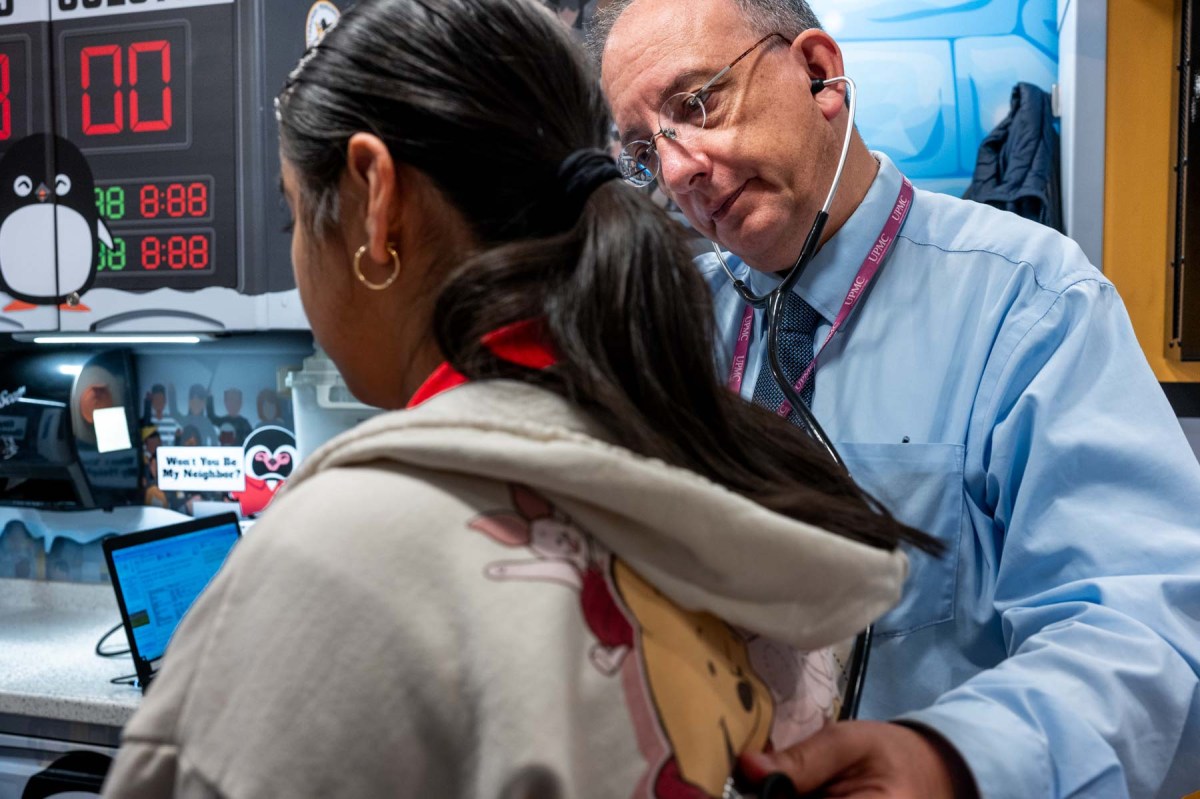

In Beechview, a free bilingual clinic cares for children of immigrants

Growing needs and rising tensions

To get the food they need for the week, a pantry participant must first maneuver through the tight streets of South Oakland. If they’re new to Pittsburgh and unfamiliar with traffic laws here, they might park in a fire lane or permit-parking spot for residents.

It’s happened often enough to create conflict with neighbors, some of whom called police to report participants who illegally parked near the pantry, or blocked traffic on Lawn Street while loading food into their cars. Pantry Program Manager Mattie Johnson once had to defuse tension when a group of neighbors confronted participants outside the pantry to complain about the disruption near their homes.

Police who arrived to enforce traffic laws were unprepared for the language diversity at the pantry. Johnson said an officer “made this one big announcement” in English, which many participants couldn’t understand. When staff used interpreters to make sure everyone got the message, “it kind of clicked to her, you know, what was going on here.”

More refugees have resettled in Allegheny County in recent years, according to data provided by the Pennsylvania Department of Human Services. It partnered with resettlement agencies to bring 746 people here in 2023 and 822 in 2022 — up from 174 in 2021. The historic high is due to people fleeing conflict and instability in countries such as Ukraine, Afghanistan, Venezuela and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, said Dana Gold, chief operating officer of Jewish Family and Community Services [JFCS], one of four resettlement agencies in the region.

Research shows they’re at risk for food insecurity after they arrive — especially if they face language barriers, which can lead to fewer job opportunities and difficulty enrolling in food assistance programs.

It’s why food pantries should develop “linguistic and cultural competency” to serve them, said Ha Ngan (Milkie) Vu, an assistant professor of preventive medicine at Northwestern University who studies food insecurity in refugee and immigrant populations. That means stocking “culturally appropriate foods” and hiring staff with the language skills to communicate with participants.

The CHS team stepped up on a recent afternoon as people from Ukraine, Afghanistan and other countries walked through the pantry doors.

An Arabic-speaking volunteer helped new participants with the intake process. Interpreters from Larimer-based Global Wordsmiths — who speak rarer languages and dialects like Dari and Pashto — were a phone call away. An assortment of fresh produce, dried legumes and canned goods was stocked on the shelves. And non-English-speaking participants could point to signs on the wall — of a lamb, pig, cow, turkey and fish — to choose cuts of meat.

There were problems to solve, too. Staff placed signs and cones around no-parking zones, and have expanded pantry hours to keep the flow of traffic moving.

Romano attended a November meeting of the Oakcliffe Community Organization, which represents residents of the South Oakland enclave, to announce the changes to neighbors who complained.

Johnson said neighbors who called police to “intentionally ticket” vulnerable participants aren’t helping. She described the plight of a low-income woman who stayed away from the pantry for weeks after she was fined $50 for a parking violation.

“It’s affecting the people that are already here to receive help, and who need it the most — especially her,” she said. “And I felt so bad because there was nothing we could do.”

Elena Zaitsoff, vice president of the Oakcliffe group, declined to comment on behalf of residents. She said CHS leadership is welcome to keep attending meetings to update the community.

Johnson hung a large sign near the pantry entrance that reads “Welcome” in 17 languages. After clashes with neighbors and a recent xenophobic comment from one participant to another, she wanted refugees and immigrants to know “that they can come here [and] we're going to try to accommodate their needs … as much as possible.”

One of her biggest hurdles? Sourcing halal meat, which is expensive and hard to find in the charitable food system.

While Pittsburgh’s district bleeds students, a few schools grow

Working toward a charitable food system for all

Halal is the Arabic word for “permitted.”

It applies to anything that’s allowed under Islamic law, but it’s most often used to describe food, said Asma Ahad, the director of halal market development at IFANCA, an Illinois-based halal certification organization.

An animal must be slaughtered by a Muslim using the proper method, which is considered more humane, according to IFANCA guidelines. Pork isn’t allowed, so Muslims typically eat halal beef, lamb or chicken. Suppliers avoid cross-contamination with non-halal foods.

“We see more halal-specific diets than anything,” said Johnson.

But the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, which supplies local pantries, hasn’t consistently offered halal meat. Johnson pulled up its online ordering form on a December afternoon. It allowed her to select kosher foods — eaten by followers of Jewish dietary law — but not halal ones.

“I feel like our halal families are coming in every week and we have to constantly give them fish, fish, fish,” she said. “... I don’t feel like it’s fair” that Muslims who come to the pantry can’t choose from a wide array of meats.

“I don’t think it was intentional,” she added.

It “definitely” wasn’t, said Erin Kelly, director of partner and distribution programs at the food bank. “Our inventory is constantly changing.”

A food bank spokesperson wrote in an emailed statement that partner food pantries have “low demand” for halal beef and chicken because it’s more expensive. “Thus, we tend to not keep as big of a supply” in our warehouse. But it keeps some halal meat offsite for partners who need it and encouraged pantry staff to reach out when they can’t order the items online.

“We will work with CHS and other partners that serve similar populations to ensure they have the resources to serve their community,” said the spokesperson.

Johnson asked the food bank for halal products in November. It responded to her request the day after PublicSource asked it questions about its halal inventory. She said the food bank offered to add halal chicken to its next delivery to the pantry.

A majority of food-insecure Muslims require or prefer halal foods, according to a poll by the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding, a Michigan-based think tank that studies American Muslims. Ahad said food banks and pantries are “slowly” realizing they need to do more, “but there’s still not an understanding of … why doing it right and doing it on a regular basis is critical.” The problem needs to be recognized at the federal level “so it can trickle down,” she added.

Slip sliding away: Federal funds buy out Pittsburgh homes under threat from landslides

Advocates want to expand the list of halal and kosher foods available through The Emergency Food Assistance Program, a federal program which buys healthy foods and partners with states to distribute them via food banks and pantries. They’re pushing for more equity in food stamps, too.

In the meantime, a handful of pantries in the region will keep trying to plug the holes in the system. Some are struggling to keep up with demand.

The Islamic Center of Pittsburgh runs a delivery-based pantry that offers halal meat sourced from local butcher Salem’s Market and Grill. The sign-up system filled up in a day this month — a record since it started posting the forms online a few years ago.

“I was shocked to see this,” said Pantry Manager Issam Abushaban. “That goes to show you how many people are in need and how desperate the situation is.”

He’s seen more families from Syria and Afghanistan at the mosque lately. “We tend to be a comfort zone for people who need help when they come from other places,” he added.

The Squirrel Hill Food Pantry, run by JFCS, is one of the few pantries in the county that’s open five days a week. It’s built up a network of suppliers — local and in New York — to keep shelves stocked with kosher and halal foods. Refugees often receive their first supplemental foods from the pantry, which sources culturally appropriate produce for them such as tomatillos, plantains and mangoes. Staff said they tend not to use canned goods.

“We’ve been doing this a long time,” said Gold, the JFCS executive.

But there’s still more to learn: “We were buying the wrong kind of lentils” for Afghan families, she said.

CHS secured a $51,000 grant from McAuley Ministries last month to buy halal meat and other foods. It’s awaiting the funds, searching for a local supplier and keeping a dedicated halal freezer ready.

Paiwandi, the father of four from Afghanistan, will be glad to have some options.

“We just want to have food which is halal for Muslims,” he said. “Chicken, cow and fish meat.”

If you need food assistance, dial 211 or find resources here.

Venuri Siriwardane is PublicSource’s health and mental health reporter. She can be reached at venuri@publicsource.org or on X, the platform formerly known as Twitter, @venuris.

This story was fact-checked by Delaney Adams.

This reporting has been made possible through the Staunton Farm Mental Health Reporting Fellowship and the Jewish Healthcare Foundation.